Prognostic value of combined preoperative prognostic nutritional index and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Patients with malignant tumors usually have various nutritional problems, especially for those with digestive system tumors (1,2). The correlation between nutrition and survival has become a hot spot in recent years (3). Esophageal cancer is one of malignancies featured with high mortality, and the 5-year survival rate is only 15–34% (4). Surgery remains the first choice for esophageal cancer patients with no distant metastases. Patients with esophageal cancer usually have dysphagia, leading to various nutritional problems. Impaired nutritional status accelerates tumor progression because it has a bad influence on immune function. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI), which was used to evaluate the nutritional status before surgery, has been widely reported to be associated with the prognosis of many malignant tumors, including esophageal cancer (5-7). Recently, the interaction between cancer and the inflammatory system has been increasingly demonstrated. And a series of inflammatory indexes, including neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR) and so on, have been confirmed to predict prognosis in various malignancies, also including esophageal cancer (8,9). However, the effect of these combined two indexes on the prognosis of esophageal cancer is unknown. Liu et al. demonstrated the combined index of PNI and NLR was superior to either index alone in patients with hepatic carcinoma (10). Therefore, the combination index may increase the accuracy of prognosis assessment for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) after surgery was hypothesized in our article. It also showed whether the combination index of PNI-NLR had an advantage over than that of either alone. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE Reporting Checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-19-2397).

Methods

Patients

This study was based on a retrospective analysis of 271 patients with esophageal cancer, who underwent radical surgery (the primary lesions of esophageal cancer were completely resection and postoperative pathology showed negative resection margins, and lymph nodes around the esophagus cancer were dissected) from Qianfoshan Hospital. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Qianfoshan Hospital (No. 8017556) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Because of the retrospective nature of the research, the requirement for informed consent was waived. All the patients met the following inclusion criteria: (I) first pathologically diagnosed with ESCC and was confirmed by endoscopic biopsy; (II) aged from 18–75 years old; (III) KPS ≥70; (IV) R0 resection; (V) no distant metastasis. The exclusion criteria included: (I) prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy; (II) history of another primary cancer; (III) the presence of hematologic disorders or inflammatory or autoimmune diseases; (IV) serious medical diseases that may affect survival; (V) cases of R1/R2 resection.

Study design

This was a retrospective study from a single Chinese hospital. This study was conducted in Qianfoshan Hospital from May 2009 to July 2014.

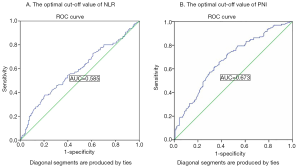

Peripheral blood samples and biochemical examination data (liver function and renal function that tested by venous blood) were obtained within 2 weeks before surgery. The PNI was calculated as follows: 10× albumin (g/dL) concentration +0.005× total lymphocyte count (mm3). The index of NLR was defined as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count. The cut-off values of PNI and NLR were determined using Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves according to the 5-year survival of all the patients. We determined the best cutoff values for PNI and NLR to be 49.1 and 3.14, respectively. And a new score system, the combined PNI and NLR score (PNI-NLR), was calculated from preoperative data as follows: patients with both an decreased NLR and an increased PNI were enrolled into group 1 (score 0, NLR ≤3.14 and PNI >49.1), those with either an elevated NLR or a decreased PNI were enrolled into group 2 (score 1, NLR >3.14 or PNI ≤49.1), and those with an increased NLR and an decreased PNI were enrolled into group 3 (score 2, NLR >3.14 and PNI ≤49.1), respectively. Clinicopathological parameters of all the patients, including age, gender and so on were collected before and after surgery. Tumor length, lymph stage were obtained from pathological and surgical reports. Before analysis, postoperative pathological staging (TNM staging) of all the patients were assessed according to the 8th version of the TNM staging system by AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) and UICC (Union for International Cancer Control). The mean postoperative follow-up period for the 271 patients was 83.7 months (range, 58–123 months). And the last follow-up date was May 30, 2019.

Statistical analysis

ROC curve analysis was used to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the PNI and NLR for predicting the 5-year overall survival (OS). And the maximum value of the Youden index was used to select the optimum cutoff point of PNI and NLR. The differences in the clinicopathologic characteristics among different subgroups were analyzed using the chi-square test or independent Sample t-test. OS was defined from the date of surgery to death due to any cause. And OS was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences inter-groups were compared using the log-rank test. Prognostic factors were evaluated using univariate and multivariate analyses with the Cox proportional hazard regression model. Variables with P value <0.1 in univariate analysis were brought into multivariate Cox proportional hazard model using a forward selection method. All the statistical tests were two sided, and P<0.05 was considered significant, and confidence intervals (CI) were calculated at the 95% level. All the data was analyzed using SPSS (version 22.0, IBM). Comparison of ROC curves among these three indexes using MedCalc.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients and ROC analysis

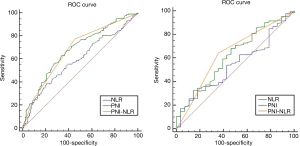

The clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 271 patients were enrolled in our study, including 221 men and 50 women (median age of 61 years old). A time-dependent ROC analysis was used to find the best cut-off values of NLR and PNI was 3.14 and 49.1, respectively (Figure 1), and then to calculate the PNI-NLR score according to the above method for every patient. All the patients were divided into three groups, that is group 1, group 2 and group 3 as described above. Using the 5-year survival rate as an end point, the area under the ROC curve of PNI and NLR was 0.673, 0.585, respectively (Figure 1). And the sensitivity and specificity rates were 63.04% and 66.17%, 57.86% and 69.39% of PNI and NLR, respectively. The area under the ROC curve was 0.685 for PNI-NLR (5-year survive as end point. And the sensitivity and specificity rates were 63.56% and 58.33% (Figure 2).

Table 1

| Variables | PNI-NLR group | PNI | NLR | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | P | PNI-high | PNI-low | P | NLR-high | NLR-low | P | |||

| Age (year) | 60.20±8.49 | 61.57±8.92 | 63.19±9.05 | 0.15 | 59.97±8.85 | 61.76±8.57 | 0.13 | 61.49±9.58 | 61.25±8.48 | 0.84 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 24 | 19 | 7 | 0.31 | 21 | 29 | 0.18 | 11 | 39 | 0.16 | ||

| Male | 80 | 102 | 39 | 119 | 102 | 71 | 150 | |||||

| TNM stage | ||||||||||||

| I–II | 57 | 68 | 16 | 0.04 | 76 | 65 | 0.52 | 35 | 106 | 0.06 | ||

| III–IVA | 47 | 53 | 30 | 64 | 66 | 47 | 83 | |||||

| N stage | ||||||||||||

| N− | 57 | 69 | 21 | 0.42 | 77 | 70 | 0.89 | 41 | 106 | 0.43 | ||

| N+ | 47 | 52 | 25 | 63 | 61 | 41 | 83 | |||||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 75 | 79 | 36 | 0.22 | 101 | 89 | 0.53 | 62 | 128 | 0.25 | ||

| No | 29 | 42 | 10 | 39 | 42 | 20 | 61 | |||||

| Drinking | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 76 | 79 | 37 | 0.12 | 102 | 90 | 0.54 | 63 | 129 | 0.19 | ||

| No | 28 | 42 | 9 | 38 | 41 | 19 | 60 | |||||

| Tumor length | ||||||||||||

| ≤5 cm | 60 | 70 | 22 | 0.47 | 80 | 72 | 0.72 | 42 | 110 | 0.29 | ||

| ˃5 cm | 44 | 51 | 24 | 60 | 59 | 40 | 79 | |||||

| Tumor location | ||||||||||||

| Upper | 11 | 10 | 3 | 0.79 | 15 | 9 | 0.37 | 7 | 17 | 0.99 | ||

| Middle | 39 | 48 | 15 | 55 | 47 | 31 | 71 | |||||

| Lower | 54 | 63 | 28 | 70 | 75 | 44 | 101 | |||||

| Differentiation | ||||||||||||

| Well | 12 | 14 | 3 | 0.25 | 14 | 15 | 0.71 | 5 | 24 | 0.27 | ||

| Middle | 60 | 78 | 24 | 87 | 75 | 51 | 111 | |||||

| Poor | 32 | 29 | 19 | 39 | 41 | 26 | 54 | |||||

NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

The baseline demographics of all the patients in different subgroups (groups 1, 2, 3) were shown in Table 1. No significant differences between the two subgroups (in different NLR subgroups or in different PNI subgroups) were noted in age, gender, smoking, drinking, TNM stage, tumor length, location, and differentiation. However, in different PNI-NLR subgroups, the TNM staging was statistically different. Patients from group3 have more patients with stage III and IVA than those from group 1 and group 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

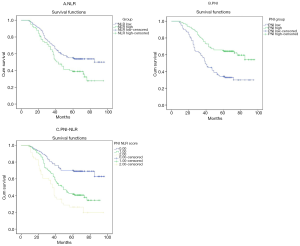

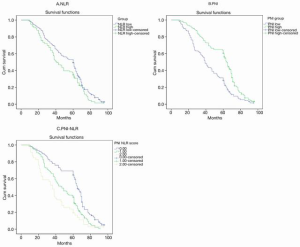

Figures 3 and 4 show Kaplan-Meier curves for 5-year survival and OS stratified by NLR, PNI and PNI-NLR. The 5-year survival and the overall survive were significantly worse in the low PNI group than in the high PNI group with both P≤0.001. The 5-year survival and the OS time were significantly longer in the low NLR group than in the high NLR group (P=0.006, P=0.026). Patients of PNI-NLR group 1 had significantly longer survival time than those of group 2 and group 3 (with P<0.001). At the time of the final analysis, 247 of 271 (91.14%) patients were dead.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

Cox univariate analysis indicated that TNM stage, lymph stage (N stage), tumor differentiation, NLR, PNI and PNI-NLR were prognostic factors for the overall survive. However, multivariate analysis revealed that TNM stage, N stage, PNI and PNI-NLR were significant prognostic factors for OS (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Age (≥60 vs. <60) | 0.654 | 0.483–1.085 | 0.185 | ||||

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.255 | 0.906–1.740 | 0.172 | ||||

| Stage (I–II vs. III–IVA) | 0.473 | 0.366–0.611 | <0.001 | 0.283 | 0.191–0.419 | <0.001 | |

| N stage (N− vs. N+) | 0.689 | 0.535–0.887 | 0.004 | 1.91 | 1.300–2.805 | 0.001 | |

| Smoking (yes vs. no) | 0.976 | 0.743–1.281 | 0.86 | ||||

| Drinking (yes vs. no) | 0.891 | 0.676–1.174 | 0.412 | ||||

| Tumor length (≥5 vs. <5) | 0.854 | 0.663–1.099 | 0.219 | ||||

| Tumor location | |||||||

| Upper | |||||||

| Middle | 0.701 | 0.445–1.104 | 0.125 | ||||

| Lower | 1.092 | 0.838–1.424 | 0.514 | ||||

| Differentiation | |||||||

| Well | |||||||

| Middle | 0.532 | 0.334–0.848 | 0.008 | ||||

| Poor | 0.742 | 0.547–0.959 | 0.024 | ||||

| NLR (≥3.14 vs. <3.14) | 1.377 | 1.050–1.806 | 0.021 | ||||

| PNI (≥49.1 vs. <49.1) | 0.505 | 0.391–0.652 | <0.001 | 0.472 | 0.364–0.612 | <0.001 | |

| PNI-NLR | |||||||

| 0 | |||||||

| 1 | 0.401 | 0.276–0.578 | <0.001 | 0.579 | 0.360–0.932 | 0.025 | |

| 2 | 0.689 | 0.484–0.981 | 0.038 | 0.704 | 0.704–0.529 | 0.016 | |

NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; OS, overall survival.

Comparison of ROC curves of these three indexes

The prognostic value of each index was confirmed by comparing the areas under the ROC curves (AUC area) calculated for the patients’ survival statuses at the OS and 5-year survival (Figure 4). As shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, the index of PNI-NLR had a higher AUC area than that of the index of PNI or NLR.PNI-NLR was superior to NLR both in the overall survive and 5-year survive (with both P<0.05). However, there were no statistical differences between the AUC areas of PNI-NLR and PNI both in the OS and 5-year survival (P>0.05). And there were also no significant differences in AUC areas of PNI when compared with that of NLR both in the OS and 5-year survival (P>0.05).

Table 3

| Variables | AUC area | Z | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | |||

| NLR vs. PNI | 0.542 vs. 0.623 | 1.272 | 0.203 |

| PNI vs. PNI-NLR | 0.623 vs. 0.641 | 0.472 | 0.637 |

| NLR vs. PNI-NLR | 0.542 vs. 0.641 | 2.215 | 0.027 |

| 5-year survival | |||

| NLR vs. PNI | 0.585 vs. 0.673 | 1.943 | 0.052 |

| PNI vs. PNI-NLR | 0.673 vs. 0.685 | 0.028 | 0.813 |

| NLR vs. PNI-NLR | 0.585 vs. 0.685 | 2.844 | 0.004 |

NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; AUC, areas under the ROC curve.

Discussion

Esophageal cancer is a malignant tumor characterized by high morbidity and mortality. ESCC is the major type of esophageal cancer, especially in China. Esophagectomy is still the first choice for patients with localized esophageal cancer. Due to the high risk of postoperative complications, careful consideration of surgery is very necessary, especially for the elderly patients. The nutritional status of cancer patients before surgery is closely related to their postoperative complications and survival (11). Esophageal cancer patients usually have malnutrition and weight loss before diagnosis. It is more important to choose a more appropriate way to assess the nutritional status of patients. PNI that reflects nutritional status and was found to be closely associated with survival in patients with various malignancies including esophageal cancer (5-7). Kubo et al. showed that preoperative PNI was a prognostic marker for survival in patients with ESCC. And the 5-year survival rate in the high PNI and low PNI groups were 67.2% and 41.2% (P=0.007). However, no significant differences were noted between the high PNI group and the low PNI group in postoperative complications and TNM stage (5). Another paper showed that PNI was significantly associated with tumor length, TNM staging and was a predictive factor for long-term survival in patients with ESCC (12). However, Sun et al. showed that PNI had no significant correlation with prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer. And our paper showed that there was no significantly correlation between PNI and TNM stage (Table 1) (13). The reason for this discrepancy may be the differences in the cutoff value for PNI. And there is also controversy on the selection of optimal cut-off value for PNI to predict survival. The cut-off value of PNI is usually 45, because 45 is defined as moderate to severe malnutrition. Other cut-off values such as 44, 42, 52 are also reported (11,12). The optimal cutoff value of the PNI was set at 49.1 in our article, which was the maximal Youden index calculated from ROC curve. The Kaplan-Meier curves of PNI showed that the patients from high PNI group had longer survive time than the patients from the low PNI group. PNI can serve as an index of prognosis for patients with ESCC. Recently, growing evidence has indicated that inflammatory markers including NLR are significantly correlated with progression and prognosis of various malignancies (14,15). A meta analysis involving 1,633 patients with esophageal cancer demonstrated that high NLR was associated with poor OS and disease-free survive (DFS) (16). Another meta analysis showed that the elevated NLR was associated with the depth of tumor invasion, tumor size, TNM stage, and tumor differentiation. And the elevated NLR was also demonstrated to be closely related to the poor survival of patients with ESCC (14). Vulliamy et al. showed that NLR has a high sensitivity in the detection of postoperative complications following esophageal resection (17). Some clinical trials also showed that the increased NLR was associated with significantly worse DFS and OS in both univariate and multivariate analysis (18,19). There are many inflammatory indexes related to the prognosis of patients with ESCC, NLR has the largest number of reports and relatively high credibility, so we choose NLR instead of other indexes as a prognostic factor. However, the optimal cutoff value of NLR for patients with esophageal cancer is not clear. Previous studies showed that NLR cutoffs value ranging from 1.9 to 5 were the optimal cutoff value for survival prognosis of patients with esophagus cancer (14,16,18,19). The reason for the heterogeneity is may be the different choices of the survival time as the end point. In our study, the optimal cutoff value of NLR was 3.14. This result is consistent with previous studies. However, the value of the combination PNI and NLR to the prognosis of esophageal cancer has not been reported. Liu et al. showed that the index of PNI combined with NLR was more sensitive in survival prognosis than that of either alone in patients with hepatic carcinoma (10). From this article, the group with both high PNI and low NLR has the longest survival than the other two group with low PNI or high NLR. Our article also showed that single PNI or NLR or PNI-NLR is a predictive factor for survival in patients with ESCC (Figures 3,4). However, NLR or PNI was not found to be associated with tumor differentiation, TNM stage, and lymph stage in our article (Table 1). But PNI-NLR score was found to be significantly correlated with TNM stage in our article (Table 1). This may be the reason that PNI-NLR serve as a prognostic index of ESCC was superior to the index of PNI or NLR. Although the AUC area of PNI-NLR was larger than that of NLR and PNI in both OS and 5-year survival, there was no significant differences between PNI-NLR and PNI (P>0.05, Table 3). The reason may be that the sample size is too small in our article. And this result still requires more clinical trials to confirm. Our article showed that the index of PNI-NLR was significantly superior to NLR in survival prognosis of patients with ESCC (P<0.05, Table 3, Figure 2). The index of PNI-NLR was not significantly superior to PNI in survival prognosis (Table 3, Figure 2). And there was also no significant differences in the AUC areas between PNI and NLR (Table 3, Figure 2). Univariate analysis identified PNI-NLR, NLR and PNI as significant prognostic factors for OS of ESCC, while Cox multivariate analysis determined that only PNI-NLR and PNI were the independent factors to predict survival. This result may be different from the previous articles, and the reason may be related to the differences between crowd selection and the choices of optimal cutoff value. And the differences in single factor selections and in the choices of P values when entering the COX analysis may also cause this heterogeneity.

The mechanism of the correlation between PNI or NLR and survival in patients with ESCC is still not clear. We believe that cancer progression is affected by both the cancer cells and immune system of patients. Recently, albumin has been shown to help stabilize cell growth and DNA replication to protect against tumorigenesis (20,21). Albumin has been reported as an independent prognostic factor for patients with ESCC (22). Lymphocytes are showed to inhibit the proliferation and invasion of tumor cells via cytokine-mediated cytotoxicity (23). The increased neutrophils have been proven to be associated with a poor prognosis of cancer through the promotion of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis (24,25). Moreover, previous studies showed that neutrophils inhibit T cells to promote tumor progression (26). In summary, malnutrition has weakened the immune system, lowered the response to treatment, and consequently has caused poor survival (27,28). In addition, inflammation can also lead to changes in the human immune environment, thus regulating the occurrence and metastasis of malignancies (29). The new index of PNI-NLR can simultaneously reflect the body’s immune function and nutritional status. And in addition to tumor markers, PNI-NLR may be used as an index to predict survival in patients with ESCC, with the advantages of economical and easily measurable.

There are still several limitations of our study. Firstly, the data of this study was obtained retrospectively. Secondly, the value of PNI and NLR were not gotten from the same time before surgery, although most were gotten within one week before surgery. Lastly, there is a lack of uniformity due to the differences in postoperative adjuvant therapies. Larger clinical studies still need to be performed to confirm these findings. In conclusion, the index of PNI-NLR or single PNI may be useful index for estimating the prognosis of patients with ESCC after surgery in our article.

Conclusions

Preoperative PNI-NLR was an independent predictor of survival of patients with ESCC. The index of PNI-NLR can improve the accuracy of prognoses for patients with ESCC than the index of NLR.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE Reporting Checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-19-2397

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-19-2397

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr-19-2397). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Qianfoshan Hospital (No. 8017556) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Because of the retrospective nature of the research, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Steenhagen E, van Vulpen JK, van Hillegersberg R, et al. Nutrition in peri-operative esophageal cancer management. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;11:663-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao R, Wang Y, Huang Y, et al. Effects of fiber and probiotics on diarrhea associated with enteral nutrition in gastric cancer patients: A prospective randomized and controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8418. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayne ST, Playdon MC, Rock CL. Diet, nutrition, and cancer: past, present and future. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:504-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1090-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kubo N, Ohira M, Tamura T, et al. Prognostic significance of baseline nutritional index for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after radical esophagectomy. Esophagus 2017;14:84-90. [Crossref]

- Sakurai K, Ohira M, Tamura T, et al. Predictive potential of preoperative nutritional status in long-term outcome projections for patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:525-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeda K, Shibutani M, Ohtani H, et al. Low nutritional prognostic index correlates with poor survival in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer following palliative resection of the primary tumor. World J Surg 2014;38:1217-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watanabe M, Ishimoto T, Baba Y, et al. Prognostic Impact of Body Mass Index in Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:3984-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan W, Sun Z, Xiang Y, et al. The correlation between high body mass index and survival in patients with esophageal cancer after curative esophagectomy: evidence from retrospective Studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2015;24:480-8. [PubMed]

- Liu C, Li L, Lu WS, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte Ratio Plus Prognostic Nutritional Index Predicts the Outcomes of Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Transarterial Chemoembolization. Sci Rep 2017;7:13873. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto H, Okamoto Y, Kawai A, et al. Prognosis Prediction for Postoperative Esophageal Cancer Patients Using Onodera’s Prognostic Nutritional Index. Nutr Cancer 2017;69:849-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feng JF, Chen QX. Significance of the prognostic nutritional index in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:1-7. [PubMed]

- Sun P, Zhang F, Chen C, et al. Comparison of the prognostic values of various nutritional parameters in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma from Southern China. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:484-91. [PubMed]

- Huang Y, Sun Y, Peng P, et al. Prognostic and clinicopathologic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:1165-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haram A, Boland MR, Kelly ME, et al. The prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: A systematic review. J Surg Oncol 2017;115:470-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang X, Huang Y, Feng JF, et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2015;8:789-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vulliamy P, McCluney S, Mukherjee S, et al. Postoperative Elevation of the Neutrophil: Lymphocyte Ratio Predicts Complications Following Esophageal Resection. World J Surg 2016;40:1397-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yutong H, Xiaoli X, Shumei L, et al. Increased Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio Is a Poor Prognostic Factor in Patients with Esophageal Cancer in a High Incidence Area in China. Arch Med Res 2015;46:557-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharaiha RZ, Halazun KJ, Mirza F, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of postoperative disease recurrence in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:3362-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouyang X, Dang Y, Zhang F, et al. Low Serum Albumin Correlates with Poor Survival in Gastric Cancer Patients. Clin Lab 2018;64:239-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemio-Logical literature. Nutr J 2010;9:69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao Q, Chen S, Feng JF. A novel inflammation-based prognostic index for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: neutrophil lymphocyte ratio/albumin ratio. Oncotarget 2017;8:103535-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ray-Coquard I, Cropet C, Van Glabbeke M, et al. Lymphopenia as a prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced carcinomas, sarcomas, and lymphomas. Cancer Res 2009;69:5383-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moses K, Brandau S. Human neutrophils: Their role in cancer and relation to myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Semin Immunol 2016;28:187-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uribe-Querol E, Rosales C. Neutrophils in Cancer: Two Sides of the Same Coin. J Immunol Res 2015;2015:983698. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hao S, Andersen M, Yu H. Detection of immune suppressive neutrophils in peripheral blood samples of cancer patients. Am J Blood Res 2013;3:239-45. [PubMed]

- Ji W, Zheng W, Li B, et al. Influence of body mass index on the long-term outcomes of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who underwent esophagectomy as a primary treatment: A 10-year medical experience. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura I, Shibata M, Gonda K, et al. Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor are increased and correlate with malnutrition, immunosuppression involving MDSCs and systemic inflammation in patients with cancer of the digestive system. Oncol Lett 2013;5:1682-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Labiano S, Palazon A, Melero I. Immune response regulation in the tumor microenvironment by hypoxia. Semin Oncol 2015;42:378-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]