Integrative review: patient and provider factors related to hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with liver cirrhosis

Introduction

Cirrhosis of liver is an end stage of chronic liver disease whose prevalence is on the rise due mostly to viral hepatitis (particularly Hepatitis B & C), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholism (1). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary cancer of the liver and the fifth most prevalent cancer worldwide, with rising prevalence seen in the United States (2). The major risk factor for the development of HCC is cirrhosis of the liver, with cirrhosis found in more than 80–90% of liver cancer patients (2). The American Association for Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) has recommended surveillance of patients with cirrhosis for HCC using ultrasound (US) of abdomen every 6-month interval as a cost-effective intervention to reduce mortality and improve survival. However, it is widely known that patients with cirrhosis are not being routinely screened, and surveillance rates range around 30–40% (3-5), though rates as low as 1.7–17.4% are seen when surveillance is defined as any imaging of abdomen within 6 months (6-10)

HCC, which is the most prevalent of liver cancers, has an increased incidence in all races in the birth cohort of persons born between 1945–1965 due to higher rates of hepatitis C in this group. The strongest predictor of HCC incidence is hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, followed by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and alcohol related liver disease (11). HCC incidence has increased 2.5-fold, and HCC mortality has tripled since 2001 (12). The 5-year cumulative risk for development of HCC is 5–30% in patients with cirrhosis (2). The key to survival of HCC is early detection. HCC detected early can achieve 5-year survival rates near 50–70% with resection and transplantation vs. 3-year survival of 8% if there are later signs of disease (13).

In a large robust randomized controlled study HCC surveillance (n=18,816) showed clear benefits, the patients in the surveillance arm had a 37% decrease in mortality despite less than optimal adherence to surveillance recommendations (14). Surveillance for HCC is the recommendation by all the major international liver associations including the AASLD in the United States (15), the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of Liver Disease (16), and the European Association for the Study of Liver (17). Most importantly, surveillance of HCC in high risk patients, including patients with cirrhosis, remains the standard of care.

Ultimately, the evaluation of the factors that are associated with surveillance of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is essential to clinical practice. The purpose of this integrative review is to evaluate the current state of the literature and to determine the factors associated with the surveillance of HCC in patients with cirrhosis, in order to understand the underlying variables and design interventions that influence surveillance behavior.

Methods

Literature search

An exhaustive review of the literature was completed to evaluate the factors related to lower rate of HCC surveillance in cirrhotic patients, to better understand the causes. Four electronic databases were searched, CINHAL, SCOPUS, Cochrane and PubMed using search terms cirrhosis, adherence, compliance, HCC, screening and surveillance restricted to articles from the United States since 2005, when the AASLD guidelines were formalized (15). Studies looking at patients from outside of the United States were excluded, as the unique characteristics of the United States insurance markets are not applicable to other countries and insurance and co-pay issues may influence surveillance behaviors. Only studies that considered causes of HCC surveillance in adults with cirrhosis in the outpatient setting were included. Excluded articles were those studies that discussed prevalence without examining cause, guidelines, inpatient studies, studies with patients less than 18 years old, or studies that looked at adherence to variceal surveillance guidelines, alfa-fetoprotein (AFP) surveillance alone, medication or diet adherence. Studies that evaluated patients after 2005 were included, as that is when the first AASLD guidelines recommending surveillance were initially issued (15), and the presence of guidelines should positively influence surveillance behavior. Of note, AASLD surveillance guidelines were established in 2005, recommending HCC surveillance with abdominal US every 6–12 months and subsequently changed in 2011, to recommend abdominal US for HCC surveillance every 6-month interval.

Search results

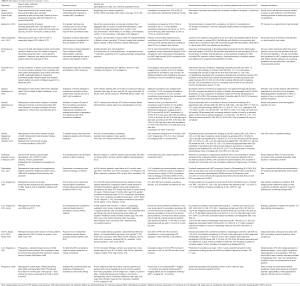

The initial database search identified 3,134 articles (Figure 1). After adjusting for duplicates, eliminating those studies that did not meet inclusion criteria, 21 articles remained. Hand searching references found an additional 7 articles, and all 28 articles were further screened. Seven studies were eliminated for not meeting inclusion criteria, including two studies that were published after 2005, but whose dates of study were before 2005 and thus did not meet inclusion criteria. The 15 publications that remained were evaluated for content, quality and relevance to clinical question. The research design, sample characteristics and factors related to HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis were extracted. Secondary evaluation also was done to examine the rate of HCC surveillance in the studies (see Table S1).

Results

Synthesis of findings

Of the 15 studies selected, 4 were provider surveys, 2 were patient surveys, and 9 were retrospective chart reviews, of which 2 were quality improvement projects. Definitions of surveillance varied among studies, from the current standard of an US of abdomen every 6-month interval, to any imaging done over a patient’s lifetime. Several factors were associated with surveillance for HCC, with provider type, setting of care and number of visits to a specialist provider being the finding most often established. Additional factors were etiology of liver disease, patient and provider related factors. Interventions to improve surveillance behaviors were also discussed. These are reported individually below.

Rates of surveillance for HCC

The definition of appropriate HCC surveillance intervals and included studies (i.e., US of abdomen or CT/MRI) varied with each study and impacted the reported surveillance rates. Type of study such as retrospective chart review, provider survey or if patients were enrolled in a clinical trial also affected the reported ranges of surveillance. When proper surveillance was defined as US of abdomen every 6 months, rates were very low, ranging from 1.7–17.4% (6-10,18).

Rates of surveillance for HCC using any imaging modality completed within a 12-month period were higher with a much wider range, with rates 13.4% to 76.4% (8-10,19-21). Rates of annual surveillance were slightly higher in patients enrolled in a clinical trial with 68.9% of patients having yearly US, and 31.3% having inconsistent adherence; of note, these patients were enrolled in a clinical trial with near perfect surveillance conditions, as patients were selected for compliance (21). Rates were also higher when the population was highly educated (63% with college degree or higher), with surveillance rates up to 76.4%. An outlier study which was a quality improvement program found 74% adherence to annual surveillance which increased to 93.2% post intervention (a reminder system for providers) (22). It is unclear how they achieved that rate, while others fell in the range below 80%. When these three studies are removed, the range falls between 13.4–51% of patients with annual surveillance (8-10,19)

Three studies defined surveillance as any imaging done within 15, 18 or 24 months, and rates of surveillance were also low, at 26% (5), 27.6% (23), and 20% (24) respectively.

The three studies that used data obtained from provider self-reported surveys reflected a higher rate of surveillance than the majority of studies, with self-reported rates of HCC surveillance ranging from 45% to 76.4% (6,25,26). However, in one of these surveys, the provider self-reported rates of every 6 months surveillance was still low, reported as 15% (6). An interesting finding in a study of VA providers was the difference in reported adherence to guidelines (70.9%) with actual adherence seen at 39.8% (26).

Factors associated with rates of HCC surveillance

Effect of type of provider, setting and visit frequency

Factors most associated with HCC surveillance was follow up with a specialist in gastroenterology or hepatology (5,7,19,24,26), increased number of visits to a specialist care provider per year (7-10), and care in an academic center (5,10). Fewer than one primary care or specialist care provider a year was negatively associated with surveillance (9). Patients followed by primary care providers for cirrhosis or diagnosis by a primary care provider were a cause of lower HCC surveillance rates (8). One study found that cirrhosis diagnosed by a surgeon to be negatively associated with surveillance (19). If the treatment site was able to refer for liver transplantation or had curative treatments available at their site, there was a higher chance of being screened for HCC (26). Care by nurse practitioners or physician assistants was associated with decreased rates of surveillance in one study (26), and higher rates (self-reported) of surveillance in another (6).

Effect of etiology of cirrhosis on adherence

Many studies linked the etiology of cirrhosis to levels of surveillance for HCC. Three studies found the highest rates of surveillance with the diagnosis of any viral hepatitis (5,8), or hepatitis C (18). The diagnosis with the lowest rates of surveillance was non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (7,9,19). Non-viral, non-NASH cirrhosis was also associated with low adherence to surveillance guidelines (19). However, there was conflicting data related to alcoholic cirrhosis as a factor in surveillance with one study finding a positive association with surveillance (5) and one finding it negatively associated with surveillance (24).

Patient level factors

Patient declining surveillance or not going for ordered surveillance was not seen as a major factor in low surveillance rates, with patient’s not going for ordered surveillance in 6% of patient’s (23), and 14.3% (24). African American race was identified as a factor in decreased surveillance rates in two studies (7,9). Complete adherence to all follow up appointments was also associated with greater surveillance frequency (21).

Two studies directly surveyed patients regarding HCC surveillance facilitators and barriers with different populations—one looked at a predominantly Caucasian, well-educated population (20) and another in an urban safety net hospital (18). These surveys revealed that patient knowledge that cirrhosis was a risk factor for HCC was associated with higher HCC surveillance rates in one patient survey (18) and patient involvement in their care and decision making process was associated with increased surveillance, with surveillance rates increasing from 62.5% in patients who were not involved in their care, to 76.4% in patients involved in their care (20). Presence of patient perceived barriers was negatively associated with HCC surveillance (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.25–0.70)—these included difficulty scheduling imaging (30.5%), costs of surveillance test (25.3%), uncertainty about where to get surveillance tests (19.6%) and difficulty with transportation (17.3%) in one study which utilized patient surveys (18).

Other patient factors were associated with HCC surveillance, though each of the following factors was seen in only one study and not across studies. Long distance (>35 miles) from home to place of care was seen as a factor in one study (7). Clinical factors that were positive predictors of surveillance included a history of a decompensation from a cirrhotic event, patients with at least one component of metabolic syndrome (8) and platelet count greater than 150,000/mm3 (21). Medicare dual eligible insurance (5) and general insurance type (8) was associated with increased probability of surveillance. Gender’s effect on surveillance rates had contradictory findings with female sex being associated with increase probability of surveillance (5) in one study, and male gender associated with higher rates in another (9). Lower rates of surveillance was associated with increasing age (5).

Provider related factors

Two surveys of primary care providers that managed cirrhotic patients reported they did not order surveillance because they were not aware of guidelines, feeling that they had more important issues to deal with than HCC surveillance, incorrect knowledge about proper surveillance, difficulty communicating with patients about surveillance, and to a lesser degree, uncertainty about benefits of guidelines and cost (6,25). Primary care providers reported in a survey that they were motivated to order surveillance because of the recommendations by medical societies and that the guidelines were supported by evidence, as well as fear of malpractice (25). Failure of the provider to recognize liver disease was also associated with non-adherence to surveillance guidelines (24).

Intervention level factors associated with improved HCC surveillance rates

Two studies that examined the effect of reminders in the medical record found that reminders to providers were a mechanism for improving surveillance rates (22,23). In the study by Aberra et al. (22), reminders were generated to alert nursing staff when a patient’s surveillance was out of date, so they could facilitate ordering of US of abdomen, which increased the rates of surveillance from 74% to 93.2%. Alternatively, in the study by Beste et al. (23), alerts were displayed during visits that could be acted upon or ignored. This intervention increased surveillance rates by 51%.

Discussion

In most of the studies, HCC surveillance rates were low even with broad definitions of appropriate surveillance. Definitions of appropriate or consistent surveillance ranged from the current AASLD guidelines which recommends US of abdomen every 6 months, to defining surveillance as an US of abdomen in the preceding 15 months period (5). Many studies stratified surveillance as complete, incomplete and no surveillance in recognition of the low rates of surveillance. Discrepancies in the definition of appropriate surveillance, however, is often due to the change in AASLD guidelines from the 2005 version which advised US of abdomen at every 6–12 months interval with AFP, to the current guidelines updated in 2011 which recommend U/S every 6 months (15). Ultimately, despite varied definitions of adherence, any factors associated with consistent HCC surveillance are only associated with an increased chance of surveillance, since the rates of surveillance is astonishingly low, with the likelihood of surveillance decreasing with length of time after cirrhosis diagnosis (8). Though the cause of this was not clearly identified, low rates of HCC surveillance is likely related to a multitude of factors including lack of knowledge by primary care providers regarding the importance or appropriate interval of HCC surveillance, the difficulty in following surveillance guidelines that require frequent follow up, and logistical issues in scheduling tests (18).

Specialist care (gastroenterologist or hepatologist) was strongly associated with increased surveillance rates (5,19,24,26), and this is clearly due to an ability to focus on the liver during visits, without ultimate responsibility to other organ systems. An increase in number of visits to a specialist provider is also closely related to increased HCC surveillance (8-10); after acute issues are resolved, more visits allow for preventative care to be emphasized, including ordering of surveillance tests. Primary care management of cirrhosis was also associated with lower surveillance rates (8). In a primary care environment, where the provider is responsible for the care of all organ systems and care coordination, there may not be a specific awareness of the need to screen for HCC at every 6 months, and even when there is this knowledge, it may not be prioritized. Not all geographic locations have easy availability of gastroenterologists or hepatologist, but in areas where there are ample specialists, it is important to refer cirrhotic patients to them for more consistent surveillance and care.

Studies that looked at patient related factors associated with low HCC surveillance rates mostly focused on demographic difference. Two studies found some influence of insurance type on HCC surveillance rates; one study found Medicare dual eligible insurance were associated with improved surveillance rates, and anther found insurance affected rates of HCC surveillance as well (5,8), though the effect was not explicit. In the United States insurance environment where may patients have high specialist co-pays and deductibles, this may prove to have some influence on attainment of specialty care and number of visits, which has been shown to influence surveillance rates. This may be an area that requires more attention.

Two studies showed rates of HCC surveillance lower amongst African American patients (7,9). This correlates with two previous influential studies that were excluded from this review, due to study dates prior to 2005, which showed race as an influence on HCC surveillance behaviors. In a large study of patients with HCC from the veterans administration (3), non-Caucasians had lower surveillance rates than Caucasians, particularly African Americans (4). A separate large study evaluating data from the SEER database also showed the lowest rates of HCC surveillance amongst African American patients (4).

An interesting finding by Singal (9) was that the failure of providers to recognize liver disease is related to lower surveillance behaviors. Failure to recognize cirrhosis is of course, linked to lower rates of surveillance. NASH cirrhosis was the diagnosis least likely to be screened (9,19), and this may be due to the difficulty diagnosing cirrhosis in this population. This points to the need to increase focus on patients with fatty liver, and identify those patients at greatest risk for NASH and cirrhosis and to follow them appropriately. As NASH overtakes viral hepatitis as the leading cause of cirrhosis in patients, this will prove to be more significant an issue moving forward.

Finally, studies found that reminders in the electronic health record increased surveillance rates (22,23), which points to the idea that increased organizational focus on surveillance cirrhotic patients for HCC, would likely increase the rates of surveillance in these patients. Offering financial incentives to providers such as those for colonoscopy and mammogram may have a positive effect on surveillance rates. From a patient perspective, lack of institutional support can also affect surveillance rates- barriers to surveillance such as cost of imaging, difficulty in scheduling imaging tests, and cost of imaging can influence surveillance rates (18). Further studies related to organizational supports and barriers that affect surveillance rates should be explored. Furthermore, patient engagement in their own care was associated with increased surveillance (20), raising the possibility that patients can influence their provider’s behavior.

Limitations

The reasons for non-surveillance of HCC in patients are complex and difficult to ascertain. Though this study showed some clear data related to patient and provider characteristics that affect surveillance behavior, there is not a clear target for intervention. The studies included in this review include retrospective chart reviews and surveys, which each have distinct limitations. Retrospective chart review misses unmeasured confounders, and often has missing data such as imaging tests done and not captured. Surveys depend on self-report and are dependent on response rates, which are low in all included studies. In the one study that sought to validate provider reports against actual data, there was a large discrepancy between reported rates of surveillance and actual surveillance tests performed (26). Furthermore, due to the cross-sectional nature of most studies included in this review, there is limited information about surveillance behaviors over time. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the surveillance rates are generally low across studies and the reason for this was not clearly identified.

Implications for practice

The main finding of this study is that specialist care such as gastroenterologist and/or hepatologist, setting of care, and number of visits to a provider has the greatest influence of surveillance behaviors. However, specialty care is limited in many areas and primary care follows patients with cirrhosis in most cases, with only 20–40% of all cirrhotic patients followed by a specialist (4). Therefore, intervention in terms of increasing knowledge of current guidelines at the level of primary care is clearly warranted to improve surveillance rates. One compelling study pointed to the lack of cirrhosis diagnosis a significant risk factor for lack of surveillance, and increased education related to identification of cirrhotic patients should also be emphasized. Furthermore, the role of cost of healthcare as it affects surveillance behaviors has not been fully studied. In the current healthcare environment in the United States where patients often pay high co-pays and deductibles, this may have a role in surveillance behaviors as well, especially as it influences number of visits to a provider, and uptake of specialist care, which are known to influence surveillance behavior. In cases where providers were prompted to order screening by a reminder, rates were higher, pointing to the idea that organizational supports can influence surveillance rates positively. Finally, surveillance of patients with cirrhosis for HCC is low, irrespective of most factors, and a greater understanding of this phenomenon is clearly needed through further focused study.

Conclusions

The findings from the integrative review point to varied patient, provider and organizational factors that influence whether a patient with cirrhosis is screened for HCC or not. Early detection of HCC is important to improve survival in HCC, and surveillance rates are very low across studies. It is important that we continue to address factors that influence surveillance behaviors in providers to improve these rates of surveillance and ultimately, improve survival in patients with cirrhosis.

Full table

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Patricia Bruckenthal for her help.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2017.03.80). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The Epidemiology of Cirrhosis in the United States: A Population-based Study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:690-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1118-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, et al. Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:85-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, et al. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology 2010;52:132-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmer LB, Kappelman MD, Sandler RS, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in a Medicaid cirrhotic population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013;47:713-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dalton-Fitzgerald E, Tiro J, Kandunoori P, et al. Practice patterns and attitudes of primary care providers and barriers to surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:791-8.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldberg DS, Taddei TH, Serper M, et al. Identifying barriers to hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in a national sample of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017;65:864-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldberg DS, Valderrama A, Kamalakar R, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Among Cirrhotic Patients With Commercial Health Insurance. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:258-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singal AG, Li X, Tiro J, et al. Racial, social, and clinical determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance. Am J Med 2015;128:90.e1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong CR, Garcia RT, Trinh HN, et al. Adherence to screening for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis B in a community setting. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:2712-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Altekruse SF, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancer. Cancer 2016;122:1312-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, et al. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1471-82.e5; quiz e17-8.

- Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, et al. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology 1999;29:62-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2004;130:417-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruix J, Sherman MAmerican Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2010;4:439-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Association For The Study Of The Liver. European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farvardin S, Patel J, Khambaty M, et al. Patient-reported barriers are associated with lower hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance rates in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017;65:875-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patwardhan V, Paul S, Corey KE, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening rates vary by etiology of cirrhosis and involvement of gastrointestinal sub-specialists. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:3316-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singal AG, Volk ML, Rakoski MO, et al. Patient involvement in healthcare is associated with higher rates of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:727-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singal AG, Nehra M, Adams-Huet B, et al. Detection of hepatocellular carcinoma at advanced stages among patients in the HALT-C trial: where did surveillance fail? Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:425-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aberra FB, Essenmacher M, Fisher N, et al. Quality improvement measures lead to higher surveillance rates for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:1157-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beste LA, Ioannou GN, Yang Y, et al. Improved surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma with a primary care-oriented clinical reminder. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:172-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singal AG, Yopp AC, Gupta S, et al. Failure rates in the hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance process. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:1124-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGowan CE, Edwards TP, Luong MU, et al. Suboptimal surveillance for and knowledge of hepatocellular carcinoma among primary care providers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:799-804. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Serag HB, Alsarraj A, Richardson P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening practices in the Department of Veterans Affairs: findings from a national facility survey. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:3117-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]