Inflammation-based markers can predict the prognosis of geriatric patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy

Introduction

Scientists have investigated the close relationship between cancer and inflammation disease for many years. It is well-recognized that cancer associated with microorganism chronic infection, for example, hepatitis B virus (HBV) with hepatic cancer, EB-Virus with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The individuals of inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, have an increased risk of colorectal cancer (1). In recent years, as Mierke, C.T suggested (2), inflammatory reactions play a vital role in tumor proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis (3-6).

Many indicators in the blood increase not only as inflammation appears but also when cancer occurs (7-9), including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP) and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). As a glycoprotein, CEA is only produced by gastrointestinal tissue in fetal development, and the production ceases before birth. However, it is usually augmented in the presence of gastrointestinal or other adenocarcinomas. CA 19-9 is elevated mainly in lung cancer and cancers of the digestive system, including pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinoma and CRC. LDH, an enzyme existing in nearly all living cells, can catalyze the conversion of lactate to pyruvic acid and back. It is well known that many tumors can express high levels of LDH (10), including colorectal cancer (11), non-small cell lung cancer (12), lymphoma, breast and gynecologic cancers (13). CRP, an inflammatory marker, is elevated in many types of cancer (14) and is discovered to be significantly elevated in lung cancer (14) and colorectal cancer (15). NLR, used as a marker of subclinical inflammation in medicine, is associated with poor prognosis in many types of cancer (16). These markers are inexpensive to test and are readily available for standard examination before treatment, so we could use them to conveniently stratify patients in the clinical practice with little expense.

Colorectal cancer is ranked as the fourth most prevalent cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the US, as indicated by the latest statistics (17). Age has been confirmed as the most important risk factor for developing colorectal cancer in epidemic studies (18). In the UK, over 66.7% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer were older than 65 years according to data collected between 2007 and 2009. By contrast, elderly patients are often excluded in clinical trials for their limited regenerative ability, lower resistance to disease, syndromes and sicknesses, and more comorbidities compared with young adults (19,20).

Since no previous studies about the effect of inflammation on the efficacy of chemotherapy and the prognosis in colorectal cancer for the geriatric population were carried out, the present study was undertaken to elucidate this problem by studying elderly patients with MCRC at our institution. The palliative medical treatment for those patients included chemotherapy alone or combined with targeted therapy, the latter therapy account for less than 20%. Most of elder patients couldn’t afford the expense of targeted therapy and some with poor physical status couldn’t tolerate intensive therapy. Therefore, this study, formulating the effect of different inflammatory factors on survival or first-line chemotherapy efficacy in elderly patients with MCRC, focused on groups with chemotherapy alone in first-line treatment.

Methods

Patient eligibility

Patients above the age of 65 years, diagnosed with MCRC, and treated with first-line chemotherapy at our institution between January 1, 2004 and October 1, 2015 were identified. All patients included have been histologically proven CRC at primary tumor sites. And the diagnosis of metastasis diseases was based mainly on clinical and radiologic findings while histological evidence for few patients. At least two cycles of palliative chemotherapy were given to every patient, and pretreatment values of inflammatory markers, LDH, CRP, CEA, CA 19-9 and NLR, were collected to analysis. Patients who had other cancer or acute and chronic infectious disease or received hormone treatments were excluded from our study. Basic characteristic information for all the patients was collected. The authenticity of this article has been validated by uploading the key raw data onto the Research Data Deposit public platform (www.researchdata.org.cn), with the approval RDD number as RDDA2017000366.

Laboratory measurements of LDH, CRP, CEA, CA 19-9 and NLR

The inflammatory plasma factors included in our study were measured in each included patient before treatment initiation using laboratory devices in our cancer center. LDH and CRP were included in a biochemical test performed using the Hitachi Automatic Analyzer 7600-020 (Tokyo, Japan), and CEA and CA 19-9 in serum tumor marker tests were measured using the Roche Elecsys 2010 Chemistry Analyzer (Basel, Switzerland). NLR was counted as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and neutrophils and lymphocytes were measured by routine blood examination (XE-5000TM Automated Hematology System). The normal range of CEA and CA 19-9, LDH and CRP in blood were 0–5 ng/mL, 0–35 U/mL, 109–245 U/L, and 0–8.2 mg/L. NLR, as a specific value, did not have standard normal range.

Patient follow-up

The primary endpoint of the current study was to define the prognostic value of LDH, CRP, CEA, CA19-9 and NLR levels with regard to OS in patients with MCRC who were treated with palliative chemotherapy. The secondary endpoint was PFS for first-line palliative chemotherapy. OS was defined as the time from the initiation of palliative first-line chemotherapy to the date of death or the last day of follow-up, September 18, 2016, and PFS was defined as the time from the start of chemotherapy to disease progression or death caused by cancer after first-line treatment.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequencies and descriptive statistics were used to compare basic patient characteristics. The univariate analyses between prognostic variables and OS or PFS were performed using Kaplan–Meier curves with long-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to evaluate the association between selected prognostic factors and OS or PFS in multivariate models and hazard ratio (HR) and its associated 95% confidence interval (95% CI) estimation. Only variables associated with highly significant P value (<0.05) at the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. All markers were sought out to provide a new cut-off point in our study that could classify all patients into two groups with the most significantly different overall survival time. The cut-off values for inflammatory markers were determined according to the minimum P value method (21-25). It’s a procedure that selects the cut-off point that minimizes the significance level of a log-rank test with comparison of the two groups defined by the cut-off point. This procedure adjusts the significance level for maximal selection (24). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the prognostic values of combination of CEA with CA 19-9. We set the combination of CEA with CA 19-9 as one value which contained three categories: CEA ≥85 ng/mL and CA 19-9 ≥32.97 U/mL; CA 19-9 ≥32.97 U/mL or CEA ≥85 ng/mL; CEA <85 ng/mL and CA 19-9 <32.97 U/mL. All analyses considered P<0.05 as statistically significant results.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 186 patients, 135 (72.6%) males and 51 (27.4%) females, with 1,028 cycles of first-line chemotherapy and a mean of 5.5 cycles, were followed up for 5 to 95.1 months (median 19.9 months). At the end of our study, 32 patients (17.2%) dropped the study and 134 patients (72.0%) died. 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rate were 72.8%, 22.8% and 10.2%. In order to avoid bias, the monitoring time for all survivors was more than 2 years. All patients were more than 65 years of age with a median age of 72 (range, 65–85). OS was analyzed in all patients and PFS was analyzed in 99 patients (53.2%). Median PFS for first-line chemotherapy was 6.70 months (95% CI, 5.74–7.66) and median OS was 25.62 months (95% CI, 21.07–30.18). Primary tumor sites were divided into right- (ascending and transverse colon) and left-sided (descending and sigmoid colon and rectum) colorectal cancer. We divided treatment regimens mainly into five group: FOLFOX, oxaliplatin plus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus calcium folinate (CF); FOLFIRI, irinotecan plus 5-FU plus CF; CapOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin; CapIRI, capecitabine plus irinotecan; capecitabine. After univariate analysis, we found it was no significant difference of OS between each different treatment regimens. And there was still no significant difference of OS in mono-chemotherapy and combination chemotherapy. The basic clinical and pathologic characteristics of all cases and the association of these characteristics with OS are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Number | Percentage (%) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.151 | ||

| Male | 135 | 72.6 | |

| Female | 51 | 27.4 | |

| Age (median 72 years) | 0.208 | ||

| >72 | 91 | 48.9 | |

| 65–72 | 95 | 51.1 | |

| Karnofsky Performance Status | — | ||

| <80 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥80 | 136 | 73.1 | |

| Missing | 50 | 26.9 | |

| Primary tumor sites | 0.479 | ||

| Right-sided | 50 | 26.9 | 0.224b |

| Left-sided | 66 | 35.5 | |

| Rectal | 65 | 34.9 | |

| Missing | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Pathological grading | 0.078 | ||

| Grade I | 6 | 3.2 | 0.032c |

| Grade II | 112 | 60.2 | |

| Grade III | 34 | 18.3 | |

| Missing | 34 | 18.3 | |

| Clinical stage IV | 186 | 100.0 | — |

| Liver metastasis | 0.061 | ||

| Yes | 128 | 68.8 | |

| No | 58 | 31.2 | |

| Celiac metastasis | 0.069 | ||

| Yes | 42 | 22.6 | |

| No | 144 | 77.4 | |

| Lung metastasis | 0.893 | ||

| Yes | 64 | 34.4 | |

| No | 122 | 65.6 | |

| First-line chemotherapy | 0.420 | ||

| FOLFOX | 72 | 38.7 | 0.994d |

| FOLFIRI | 18 | 9.7 | |

| CapOX | 59 | 31.7 | |

| CapIRI | 9 | 4.8 | |

| Capecitabine | 28 | 15.1 |

a, P values between patients’ characteristics and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test. b, P value was calculated when primary tumor sites was divided as right-sided and left-sided colorectal cancer. c, P value was calculated when first-line treatments were divided as grade I–II and grade III. d, P value was calculated when first-line chemotherapy was divided as mono-chemotherapy and combination chemotherapy. FOLFOX, oxaliplatin plus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) plus calcium folinate (CF); FOLFIRI, irinotecan plus 5-FU plus CF; CapOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin; CapIRI, capecitabine plus irinotecan.

Prognostic effect of CEA, CA 19-9, LDH, CRP and NLR on OS

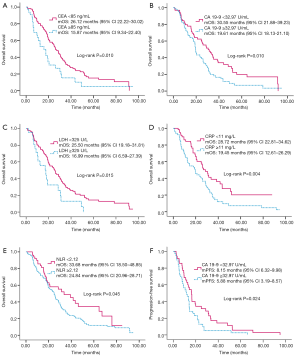

The values of LDH, CRP, CEA, CA 19-9 and NLR before the first-line chemotherapy were used in the analysis. By univariate analysis, showed in Table 2 and Figure 1, OS was most significantly reduced in the CEA ≥85 ng/mL (P=0.010), or CA 19-9 ≥32.97 U/mL group (P=0.010), and LDH ≥325 U/L (P=0.015), the CRP ≥11 mg/L group (P=0.004) and the NLR ≥2.12 group (P=0.045). Therefore, the cut-off values for CEA, CA 19-9, LDH, CRP and NLR were 85 ng/mL, 32.97 U/mL, 325 U/L, 11 mg/L and 2.12, respectively, in the subsequent analysis. In addition to these inflammation related markers, primary pathological grading (grade I–II vs. grade III: P=0.043) and celiac metastasis (P=0.060) were also included in the multivariate analysis model. As shown in Table 3, it was found that LDH (P=0.025) were independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 3).

Table 2

| Factors | Colorectal cancer | Right-sided colorectal cancer | Left-sided colorectal cancer | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients number | Median survival (95% CI), months | P value* | Patients number | Median survival (95%CI), months | P value* | Patients number | Median survival (95%CI), months | P value* | |||

| Overall survival | |||||||||||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.010 | <0.001 | 0.138 | ||||||||

| <85 | 123 | 26.12 (22.22–30.02) | 35 | 21.13 (12.95–29.30) | 87 | 28.52 (23.53–33.50) | |||||

| ≥85 | 33 | 15.87 (9.34–22.40) | 8 | 6.21 (4.62–7.80) | 25 | 19.06 (13.89–24.22) | |||||

| CA 19-9 (U/mL) | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.083 | ||||||||

| <32.97 | 67 | 30.55 (21.88–39.23) | 23 | 26.05 (12.59–39.52) | 43 | 31.47 (23.88–39.07) | |||||

| ≥32.97 | 85 | 19.61 (18.13–21.10) | 20 | 11.04 (1.81–20.27) | 65 | 23.26 (16.86–29.66) | |||||

| LDH (U/L) | 0.015 | 0.070 | 0.039 | ||||||||

| <325 | 134 | 25.50 (19.18–31.81) | 38 | 19.65 (16.37–22.92) | 95 | 26.91 (22.16–31.66) | |||||

| ≥325 | 21 | 16.99 (6.59–27.39) | 5 | 7.85 (5.67–10.04) | 16 | 17.58 (10.52–24.63) | |||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.004 | 0.416 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| <11 | 61 | 28.72 (22.81–34.62) | 16 | 20.47 (18.53–22.41) | 44 | 31.54 (22.83–40.25) | |||||

| ≥11 | 66 | 19.45 (12.61–26.29) | 20 | 12.45 (2.64–22.26) | 46 | 19.61 (16.63–22.60) | |||||

| NLR | 0.045 | 0.885 | 0.020 | ||||||||

| <2.12 | 52 | 33.68 (18.50–48.85) | 11 | 18.17 (10.41–25.93) | 41 | 39.26 (24.81–53.71) | |||||

| ≥2.12 | 131 | 24.84 (20.96–28.71) | 38 | 20.47 (12.30–28.63) | 92 | 24.94 (22.20–27.67) | |||||

| Progression-free survival | |||||||||||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.116 | 0.228 | 0.321 | ||||||||

| <85 | 63 | 7.06 (5.75–8.38) | 21 | 7.13 (3.20–11.06) | 42 | 6.74 (5.34–8.13) | |||||

| ≥85 | 12 | 6.24 (1.45–11.04) | 2 | 2.17 (no 95% CI) | 10 | 6.24 (1.41–11.08) | |||||

| CA 19-9 (U/mL) | 0.024 | 0.570 | 0.086 | ||||||||

| <32.97 | 35 | 8.15 (6.32–9.98) | 16 | 8.31 (3.23–13.40) | 19 | 8.05 (5.01–11.09) | |||||

| ≥32.97 | 39 | 5.88 (3.19–8.57) | 7 | 3.84 (0.47–7.22) | 32 | 6.24 (4.60–7.88) | |||||

| LDH (U/L) | 0.360 | 0.191 | 0.816 | ||||||||

| <325 | 64 | 7.06 (6.26–7.87) | 19 | 7.13 (3.39–10.87) | 45 | 7.06 (6.42–7.71) | |||||

| ≥325 | 10 | 4.53 (1.38–7.69) | 4 | 2.60 (0.00–7.10) | 6 | 4.53 (2.09–6.98) | |||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.847 | 0.996 | 0.575 | ||||||||

| <11 | 30 | 7.06 (6.49–7.64) | 8 | 7.13 (3.03–11.23) | 22 | 6.70 (4.14–9.27) | |||||

| ≥11 | 25 | 6.01 (5.10–6.92) | 11 | 4.67 (1.26–8.07) | 14 | 6.24 (4.92–7.57) | |||||

| NLR | 0.153 | 0.052 | 0.665 | ||||||||

| <2.12 | 30 | 5.65 (3.01–8.30) | 8 | 3.02 (0.00–6.39) | 22 | 6.74 (3.49–9.98) | |||||

| ≥2.12 | 66 | 6.64 (5.71–7.57) | 20 | 6.64 (5.99–7.29) | 46 | 6.24 (5.26–7.23) | |||||

*, P values were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; NLR, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 3

| Prognostic factors | Colorectal cancer | Right-sided colorectal cancer | Left-sided colorectal cancer | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value* | HR | 95% CI | P value* | HR | 95% CI | P value* | |||

| Pathological grading | 1.78 | 1.02–3.06 | 0.043 | 2.16 | 0.87–5.42 | 0.099 | 1.15 | 0.57–2.31 | 0.698 | ||

| Metastasis sites | 1.69 | 0.98–2.91 | 0.060 | 1.06 | 0.41–2.72 | 0.900 | 1.26 | 0.60–2.67 | 0.542 | ||

| CEA | – | – | – | 6.23 | 1.94–20.04 | 0.002 | – | – | – | ||

| LDH | 2.10 | 1.10–4.02 | 0.025 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| CRP | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.80 | 1.03–3.17 | 0.040 | ||

*, P values were calculated using the Cox-proportional hazard model. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; NLR, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; HR, hazards ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

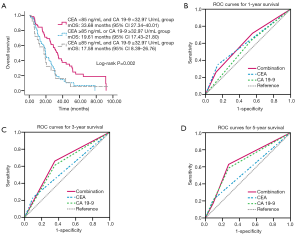

When combining the most popular prognostic factors in CRC, CEA and CA 19-9, median OS was 33.68, 19.61 and 17.58 months in groups with CEA <85 ng/mL and CA 19-9 <32.97 U/mL group, CEA ≥85 ng/mL or CA 19-9 ≥32.97 U/mL group and group CEA ≥85 ng/mL and CA 19-9 ≥32.97 U/mL group, respectively (Figure 2). In COX regression analysis, including the same factors as above, found that the combination of CEA with CA 19-9 was also an independent factor for OS (HR =1.44; 95% CI, 1.10–1.90; P=0.009). When predicting the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival, combination of CEA with CA 19-9 had higher sensitivity compared with CEA and CA 19-9 respectively, demonstrated in Figure 2. Interestingly, we found CEA had higher specificity in predicting 1-, 3- and 5-year survival.

Prognostic effect of CEA, CA 19-9, LDH, CRP and NLR on OS in right- or left-sided colorectal cancer

Further analysis was done to identify the effect of these markers on OS in right- and left-sided colorectal cancer. As indicated in Table 2, three inflammation markers, LDH (P=0.039), CRP (P=0.004) and NLR (P=0.020) were prognostic factors for OS in 131 left-sided colorectal cancer patients with lower levels of markers associated with improved OS. Similar to the prior analysis, primary pathological grading (P=0.698) and celiac metastasis (P=0.542) were also included in multivariate analysis model. As shown in Table 3, it was found that CRP (P=0.040) was an independent prognostic factor for OS. For 55 patients with right-sided colon cancer, CEA (P<0.001) and CA 19-9 (P=0.003) were prognostic factors, showed in Table 2. As shown in Table 3, it was found CEA (P=0.002) was an independent prognostic factor for OS.

Predictive effect of CEA, CA 19-9, LDH, CRP or NLR on PFS after first-line treatment

Only CA 19-9 (P=0.024) appeared to be predictive of PFS in a univariate analysis (Table 2 and Figure 1). However, it (P=0.052) was not an independent predictive factor by multivariate analysis. CEA, LDH, CRP and NLR did not have significant effects on PFS by univariate analysis (Table 2). The univariate analysis of the right- and left-sided colorectal cancer subgroups showed that no significant value was found as a predictive factor in both right-sided and left-sided colorectal cancer (Table 2).

Discussion

Inflammatory factors interacted with cancer cells on both molecular and cellular levels. On the one hand, proto-oncogenes boost expression of inflammation-associate factors and create the tumor inflammatory microenvironment; on the other hand, this specific inflammatory microenvironment promotes tumor metastasis (4). Thus, many studies have suggested that inflammatory markers could act as prognostic factors in cancer, including colorectal cancer. Elderly patients may have different anti-inflammatory intensities than the overall population as a result of their lower metabolic rate and weaker body function, and geriatric patients might suffer from more inflammation situation than a younger population because of a longer life (26-28). Therefore, we speculate that the association between inflammation and the prognosis of CRC might be closer in geriatric patients than in the younger population.

Our findings support the hypothesis that inflammation has an important effect on the colorectal cancer mortality and the short-time efficacy of first-line therapy in elderly groups. Higher levels of inflammation markers, LDH, CRP, CEA, CA 19-9 and NLR, were closely related to a poor prognosis. In addition, LDH was independent factors in predicting OS, even when pathological grading and celiac metastasis were also taken into consideration in multivariate analysis. Furthermore, CA 19-9 was predictive of poor PFS in the univariate analysis. No inflammatory factor was associated with PFS in a multivariate analysis. As we know, PFS has a shorter window of observation and is largely affected by the different regimens administered to patients in first-line therapy. Furthermore, in this retrospective study, PFS was hard to identify as accurately as OS. To elucidate the precise relationship between inflammation and short-term treatment efficacy, we need well-devised prospective studies. Anyway, we can conclude that CEA, CA 19-9, LDH, CRP and NLR could be prognostic factors for OS.

Our subgroup analysis of the relationship between OS and primary tumor sidedness showed that CEA and CRP were independent prognostic factors for right- and left-sided colorectal cancer, respectively. Right- and left-sided colorectal cancer have different clinicopathological features and reaction to cetuximab (29), and this study furthermore found different prognostic factors for them. Compared with CEA, CRP was more representative of inflammation. Thus, we suggest that inflammation has a greater effect in left-sided colorectal cancer than right-sided colorectal cancer. As the formerly published study suggested, right-sided colon cancer has high frequency of BRAF mutation, CpG island methylation phenotype (CIMP) and microsatellite instability (MSI) (30). Conversely, left-sided tumors are characterized by chromosomal instability and a gene expression profile involving the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway (31). However, the study designed to compare inflammation status in right-sided colon cancer and left-sided colorectal cancer was still not available. CEA level showed significant relation with OS in right-sided colon cancer in our study, we guess it might be on account of the bigger volume of primary tumor sites as CEA also represents tumor burden. More research is needed to verify this. Besides, no significant marker was predictive of both the PFS of right-sided and left-sided colorectal cancer in our study.

NLR has recently been recognized as a prognostic indicator. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments have shown that the cytokines produced by neutrophils and other inflammatory mediators can promote the formation of a microenvironment that is conducive to the growth of tumor cells (32). Several studies have demonstrated that high NLR levels are related to poor prognosis in colorectal cancer (33-35), which is consistent with the findings that neutrophils inhibit the activity of lymphocytes and that more lymphocytes in tumors indicate a better patient prognosis (3,4,23). One meta-analysis suggested that NLR >1.81 was associated with an adverse OS and PFS in colorectal carcinoma (HR =1.91; 95% CI, 1.53–2.39) (16). In our retrospective study in geriatric patients with MCRC, a high NLR was associated with a poorer OS, which agreed with the published reports in general patients with colorectal cancer.

In our study, we found the super prognostic role of CEA combined with CA19-9. As we all know, tumor markers CEA and CA 19-9 are tightly related to tumor formation, metastasis and recurrence. Interestingly, it is also widely recognized that CEA and CA 19-9 could be detected increasingly as inflammation occurs. In colorectal cancer, several studies demonstrated that CEA and CA 19-9 were associated with poor PFS and OS (36-38). In gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma, CEA and/or CA 19-9 are often increased, with the former having greater specificity and sensitivity. Recent data showed that the combination of preoperative CEA and CA 19-9 levels was useful for predicting the prognosis and for monitoring recurrence and metastasis after potentially curative surgery in patients with stage II colorectal cancer (39). Furthermore, one study showed that CA 19-9 could be regarded as a marker, in addition to CEA, to monitor colorectal cancer, and patients with preoperative increased CA 19-9 levels had a poorer 5-year survival than patients with preoperative increased CEA levels (40). Our study results support that CEA and CA 19-9 could be used as prognostic factors in stage IV elderly patients. Patients with both low CEA and CA 19-9 level had best OS compared to that with anyone high level and both high level. Moreover, ROC curve showed combination of CEA and CA 19-9 improved the sensitivity of 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival prediction. Interestingly, CEA had highest specificity but lowest sensitivity compared with CA 19-9 and combination of them. Thus, we think combination of them were more practicable in clinical.

CRP played an important role in Glasgow prognostic score (GPS), an inflammation-based prognostic score assessed using the serum CRP and albumin levels, and has been found to be a useful prognostic factor in several types of cancer, including colorectal cancer. In our study, high CRP was significantly related to impaired OS as an independently prognostic factor in geriatric left-sided colorectal cancer patients. LDH represented an indirect marker of tumor hypoxia, neo-angiogenesis, metastasis development and poor prognosis in many cancers (41-44). In a phase III prospective, multicenter, randomized Italian Trial in Advanced Colorectal Cancer (ITACa), the authors suggested that a high LDH value was confirmed as a marker of poor prognosis (45).

Since this study was conducted in the real-world clinical practice and not in a clinical trial, this investigation showing the relationship between inflammation-based factors and OS might contain actual significant guidance for our practice. The more significant finding was that so many inflammatory factors were found to affect the prognosis of MCRC in the special group of geriatric patients. This might indicate that there is a stronger correlation between inflammation and cancer development in elderly than in young patients. However, this study was done retrospectively with some inevitable confounding factors. PFS was analyzed among half of cases in result of missing data. Moreover, the values of inflammation-based factors were measured only before palliative treatment, and potential change of these biomarkers during treatments should be considered in this study. One analysis of the FIRRE-3 trial showed CEA were decreased faster and greater in the cetuximab arm than in the bevacizumab arm (46). Another study also emphasized that the biochemical response with a chemotherapy induced decline in CEA level may be clinically more relevant than a single preoperative CEA value (47). In the future, we plan to study whether dynamic changes in these inflammatory factors have more power to predict PFS and OS of chemotherapy and targeted therapy in geriatric patients.

Acknowledgments

Thanks Professor Jinxin Zhang studying in medical statistics in Sun Yat-sen University for statistical consultation.

Funding: Supported by

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2019.06.27). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee at the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center and the ethic approval number is YB2016-065. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained for this study and patient information was anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kalla R, Ventham NT, Satsangi J, et al. Crohn's disease. BMJ 2014;349:g6670. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mierke CT. The fundamental role of mechanical properties in the progression of cancer disease and inflammation. Rep Prog Phys 2014;77:076602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001;357:539-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002;420:860-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, et al. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell 2004;118:285-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 2004;431:461-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clevers H. At the crossroads of inflammation and cancer. Cell 2004;118:671-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cole SW. Chronic inflammation and breast cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3418-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hagemann T, Balkwill F, Lawrence T. Inflammation and cancer: a double-edged sword. Cancer Cell 2007;12:300-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldman RD, Kaplan NO, Hall TC. Lactic Dehydrogenase in Human Neoplastic Tissues. Cancer Res 1964;24:389-99. [PubMed]

- Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 expression in operable colorectal cancer: strong association with survival and activated vascular endothelial growth factor pathway--a report of the Tumour Angiogenesis Research Group. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4301-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase-5 (LDH-5) overexpression in non-small-cell lung cancer tissues is linked to tumour hypoxia, angiogenic factor production and poor prognosis. Br J Cancer 2003;89:877-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koukourakis MI, Kontomanolis E, Giatromanolaki A, et al. Serum and tissue LDH levels in patients with breast/gynaecological cancer and benign diseases. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2009;67:162-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allin KH, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Baseline C-reactive protein is associated with incident cancer and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2217-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erlinger TP, Platz EA, Rifai N, et al. C-reactive protein and the risk of incident colorectal cancer. JAMA 2004;291:585-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju124. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith RA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2015: a review of current American cancer society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:30-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartlett EE. Patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1531. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, et al. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 1999;341:2061-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosell R, Cecere F, Santarpia M, et al. Predicting the outcome of chemotherapy for lung cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2006;6:323-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boulesteix AL. Maximally selected chi-square statistics for ordinal variables. Biom J 2006;48:451-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mazumdar M, Glassman JR. Categorizing a prognostic variable: review of methods, code for easy implementation and applications to decision-making about cancer treatments. Stat Med 2000;19:113-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faraggi D, Simon R. A simulation study of cross-validation for selecting an optimal cutpoint in univariate survival analysis. Stat Med 1996;15:2203-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller R, Siegmund D. Maximally Selected Chi Square Statistics. Biometrics 1982;38:1011-16. [Crossref]

- Zhang X, Meng X, Chen Y, et al. The Biology of Aging and Cancer: Frailty, Inflammation, and Immunity. Cancer J 2017;23:201-5. [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Rane G, Dai X, et al. Ageing and the telomere connection: An intimate relationship with inflammation. Ageing Res Rev 2016;25:55-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calder PC, Bosco N, Bourdet-Sicard R, et al. Health relevance of the modification of low grade inflammation in ageing (inflammageing) and the role of nutrition. Ageing Res Rev 2017;40:95-119. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karakas Y, Dizdar O. Tumor Sidedness and Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer: Is Microbiome the Missing Link? JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1000. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, et al. Colorectal cancer: a tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut 2012;61:794-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015;21:1350-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shau HY, Kim A. Suppression of lymphokine-activated killer induction by neutrophils. J Immunol 1988;141:4395-402. [PubMed]

- Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, et al. Combination of platelet count and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is a useful predictor of postoperative survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2013;109:401-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim IY, You SH, Kim YW. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts pathologic tumor response and survival after preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer. BMC Surg 2014;14:94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kishiki T, Masaki T, Mastuoka H, et al. New Prognostic Scoring System for Incurable Stage IV Colorectal Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016;17:597-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Novis BH, Gluck E, Thomas P, et al. Serial levels of CA 19-9 and CEA in colonic cancer. J Clin Oncol 1986;4:987-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tampellini M, Ottone A, Alabiso I, et al. The prognostic role of baseline CEA and CA 19-9 values and their time-dependent variations in advanced colorectal cancer patients submitted to first-line therapy. Tumour Biol 2015;36:1519-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haas M, Heinemann V, Kullmann F, et al. Prognostic value of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, LDH and bilirubin levels in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from a multicenter, pooled analysis of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013;139:681-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, et al. Significance of CEA and CA19-9 combination as a prognostic indicator and for recurrence monitoring in patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 2014;34:3753-8. [PubMed]

- Stiksma J, Grootendorst DC, van der Linden PW. CA 19-9 as a marker in addition to CEA to monitor colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2014;13:239-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Artac M, Uysal M, Karaagac M, et al. Prognostic Impact of Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet Count, CRP, and Albumin Levels in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with FOLFIRI-Bevacizumab. J Gastrointest Cancer 2017;48:176-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang SH, Bratman SV, Su J, et al. Independent Adverse Prognosis of Elevated Serum LDH in Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2016;96:S83. [Crossref]

- Feliu J, Diez de Corcuera I, Manzano JL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of aflibercept for metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective review within an early access program in Spain. Clin Transl Oncol 2017;19:498-507. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim EY, Kim N, Kim YS, et al. Prognostic Significance of Modified Advanced Lung Cancer Inflammation Index (ALI) in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer_ Comparison with Original ALI. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164056. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Passardi A, Scarpi E, Tamberi S, et al. Impact of Pre-Treatment Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels on Prognosis and Bevacizumab Efficacy in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134732. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michl M, Stintzing S, Fischer von Weikersthal L, et al. CEA response is associated with tumor response and survival in patients with KRAS exon 2 wild-type and extended RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line FOLFIRI plus cetuximab or bevacizumab (FIRE-3 trial). Ann Oncol 2016;27:1565-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brudvik KW, Jones RP, Giuliante F, et al. RAS Mutation Clinical Risk Score to Predict Survival After Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann Surg 2019;269:120-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]