The comparison between albumin-bilirubin grade and Child-Pugh grade for assessing the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after thermal ablation: a propensity score-matched analysis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignant tumor and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (1). Local thermal ablation is a sort of minimally invasive, potentially curative interventional therapy in early-stage HCC, and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA) in particular have been extensively utilized (2). It has been suggested in a previous study (3) that the survival rate was basically the same between surgical resection and ablation for HCC according to the Milan criteria.

Closely associated with the progression of HCC, hepatic function/dysfunction is a critical influencing factor. In general, the Child-Pugh classification is routinely performed to evaluate HCC patients for their hepatic functions and it’s even vital for the majority of the common staging systems. Unfortunately, most HCC sufferers manifest aberrant liver function, even without overt liver cirrhosis. However, The C-P grade is subjected to various limitations as it involves various subjective factors, variables in the C-P grade assigned the same weight, and some of the involved are possibly interrelated, while arbitrary cutoff levels can cause the identical score assigned to the sufferers with variation in bilirubin contents (4,5). In addition, as the majority of HCC patients are categorized into C-P class A, the C-P class system inability to distinguish hepatic functions and clinical results amongst sufferers with HCC and well-preserved hepatic functions (6).

With both serum albumin and bilirubin concentrations as the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade, a new prognostic grade provides a simple and objective method to assess hepatic function. It achieves an excellent prognostic performance for HCC patients (6-9). Studies comparing the prognosis performances between the ALBI and C-P gradation in HCC cohorts, most of them displayed that the ALBI gradation performed as well as or better than the C-P grade (7,9-11). Given the ease of its applications and objectivity, the ALBI gradation has the potential as alternative to the C-P grade. In addition, it is worth noting that the ALBI score can be used to identify two distinct prognostic groups among those C-P A patients undergoing TACE, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) and sorafenib into 2 prognosis cohorts (12-14). However, it remains inconclusive to date if the ALBI scoring could faithfully indicate the state of hepatic functions for those HCC sufferers receiving thermal ablation.

Thus, we contrasted the prognosis significance of the ALBI gradation and C-P gradation in OS and RFS for those HCC patients after thermal ablation, and ALBI grade was used to identify two distinct prognostic groups for OS and RFS among those C-P A patients. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-244/rc).

Methods

Patients

The clinical, lab, and image formation data was collected from the hospital data base of 467 consecutive HCC sufferers receiving thermal ablation as initial therapy at Tianjin Third Center Hospital from January 2013 to December 2017. The Tianjin Third Central Hospital Institutional Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required. The inclusive criteria are stated below: (I) tumors meeting the Milan criteria (solitary HCC ≤5.0 cm in diameter, or two to three HCC tumors, each ≤3.0 cm in diameter); (II) no radiology proof of major portal/hepatic vein branch invasion; (III) no extrahepatic metastases; (IV) C-P A or B illness; (V) sufferers undergoing complete ablation, which was defined as no nodular or irregular reinforcement within or near the ablation zone in the arterial phase on the first contrast-reinforced kinetic CT or MRI scanning completed approximately 30 days posterior to ablation), (VI) patients with complete clinical data needed for this study.

Treatment and follow-up

The diagnoses of HCC were confirmed in line with the HCC guide lines set out by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) or by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) (15,16). The thermoablation equipment, procedures, and intervention aided technologies have been detailed in the relevant prior researches (17,18). Each procedure was completed by 3 intervention radiologists (XJ, JD, and WY, with 20, 15 and 15 years of experience in performing thermal ablation, respectively).

All of the patients recruited were followed up 30 days posterior to thermal ablation and then at a 3-month interval in the first year and a 3–6 months interval in the later years as needed. A range of routine tests were performed during each follow-up, involving physical tests, blood examinations (AFP content, serological biological chemistry), and imaging tests (chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasonographic analysis, abdominal CT, or MRI). As for OS, it was the duration starting from the date of treatment and ending with either death or the last follow-up. In respect of RFS, it was defined as the duration starting from the date of therapy and ending on the date of cancer relapse or last follow-up (no findings of relapse or loss).

C-P score and ALBI score calculation

On the foundation of the overall bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time, and the clinical discoveries of cerebropathy and ascites, the C-P scoring was 5–6 points for C-P-A, 7–9 points for C-P-B, and 10–15 points for C-P-C (19). The formula used to obtain the ALBI score is expressed as (log10bilirubin × 0.66) + (−0.085 × albumin). The ALBI scoring was: score ≤−2.60 as ALBI-1; −2.60< score ≤−1.39 as ALBI-2; and score >−1.39 as ALBI-3 (6).

Statistical analyses

The normally distributed continuous data is described as average (SD) and those values exhibiting an abnormal distribution are treated as median (range). As for the categorical data, it was analysed through two-sided χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. Survival analysis was completed via the Kaplan-Meier approach, while the log-rank test was conducted to identify the statistically significant diversities between the ALBI gradation and C-P gradation. Moreover, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were adopted to identify the risk factors for OS and RFS. Those variables with a P value of <0.10 on the univariate analysis were factored into the multivariate analysis via the forward stepwise model. Two OS-based multivariate models were applied separately to select the independent prognostic factors. One is C-P model, which includes the baseline characteristics and C-P score while excluding ALBI score. The other is ALBI model involving the baseline characteristics and ALBI score but ignoring C-P score. It was treated as statistically significant when P values <0.05 for all analyses.

Besides, PSM was performed by a 1:1 nearest-available matching arithmetic with the assistance of a ±0.22 caliper and there was no replacement for adjusting the remarkably diverse sufferer features based on C-P A patients. The analysis was carried out with 113 (ALBI-1 vs. ALBI-2) propensity-score matched observations made. The propensity scoring was acquired via a multivariable logistic regressive model with mixed methods as the variates and the 13 base line features including age, gender, tumor size, tumor number, AFP, platelet count (PLT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and creatine as covariates, which is in line with the previously finished researches. The matching model demonstrated a strong discrimination ability (C-statistic ¼ 0.759). Then, standardized differences were compared for all covariates between pre-match imbalance and post-match balance. Moreover, statistic assay was completed via the IBM SPSS program 23.0 (America) and R program 3.6.2, respectively.

Ethical consideration

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This is an observational study. The Tianjin Third Central Hospital Institutional Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Results

Baseline features and the ALBI and C-P grade comparison

An overall 467 sufferers were recruited for the present research, involving 407 men and 184 women, with a mean age of 58.7±8.45 years. The demographical and clinical characteristics of these recruited HCC sufferers were summarised, as listed in Table 1. In the entire cohort, there were 398 patients of C-P A, 69 of C-P B. As per the ALBI gradation, there were 256, 205 and 6 sufferers assigned to the group of ALBI-1, ALBI-2 and ALBI-3, separately.

Table 1

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 350 (75.0)/117 (25.0) |

| Age (years) | 58.7±8.5 |

| Tumor number (1/2/3) | 368 (78.8)/78 (16.7)/21 (4.5) |

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.4±0.8 |

| Etiology (HBV/HCV/other) | 375 (80.3)/52 (11.1)/40 (8.6) |

| Child-Pugh grade (A/B) | 398 (85.2)/69 (14.8) |

| ALBI score | −2.62±0.53 |

| ALBI grade (1/2/3) | 256 (54.8)/205 (43.9)/6 (1.3) |

| ALB (g/L) | 40.4±5.6 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 19.8±11.8 |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.3±31.4 |

| AST (U/L) | 36.7±24.8 |

| ALP (U/L) | 96.6±44.1 |

| GGT (U/L) | 69.9±105.5 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 109.4±59.4 |

| Creatine (μmol/L) | 67.4±20.8 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 120.8±310.4 |

| NLR | 2.6±1.6 |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ALB, albumin; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartic transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; PLT, platelet; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.

Among those C-P A patients, 246 (61.8%) had ALBI-1 and 152 (38.2%) had ALBI-2. While among those C-P B patients, the number of patients graded as ALBI-1, ALBI-2 and ALBI-3 are 9, 52 and 7.

Discriminatory power of C-P or ALBI grade for long-term survival

The average length of follow-up was 44 months (range: 4–79 months). Before the follow-up ended, 109 HCC patients died (23.3%). Besides, a total of 256 patients (54.8%) experienced tumor recurrence during follow-up.

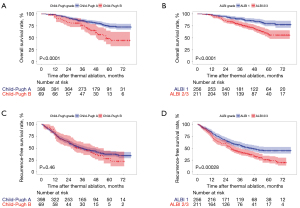

According to the Child-Pugh system, those patients with C-P A exhibited better OS than those with C-P B at 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively (98.2%, 85.9%, 74.2% vs. 89.9%, 73.2%, 45.0%, Log-rank P<0.001) (Figure 1A). While the RFS at 1, 3 and 5 years showed similarity between the patients with C-P A (78.9%, 49.8% and 36.2%) and those with grade B (78.3%, 49.1% and 28.0%) (P=0.46) (Figure 1B).

As for the OS at 1, 3 and 5 years, it was greater in those sufferers with ALBI gradation 1 (98.4%, 91.7% and 77.9%) than in those with ALBI grade 2/3 (94.3%, 78.0% and 57.6%) (P<0.001) (Figure 1C). With regard to the RFS at 1, 3 and 5 years, it was greater among those sufferers with ALBI gradation 1 (81.6%, 56.1% and 44.7%) than among those with ALBI grades 2 or 3 (75.4%, 40.5% and 24.1%) (P<0.001) (Figure 1D).

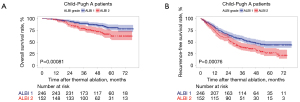

In addition, among those patients with C-P A, ALBI grade was used to classify the patients with C-P A into two different survival groups. For sufferers with ALBI gradation 1, they showed a better OS in contrast to ALBI gradation 2 sufferers (P<0.001), as can be seen from Figure 2A. Moreover, ALBI grade 1 sufferers displayed a greater RFS in contrast to ALBI gradation 2 sufferers (P<0.001), as shown in Figure 2B.

Multivariate analysis of independent risk factors for OS and RFS

According to the univariate analysis conducted for OS, the significant prognostic factors include age, tumor number, AFP level, HBV positive, PLT, GGT, ALP along with C-P scoring and ALBI gradation (P<0.05; Table 2). In order to avoid collinearity during multivariate analyses, the C-P and ALBI scoring was factored into 2 diverse logistic regressive models. On this basis, both the C-P [hazard ratio (HR) 2.411; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.581–3.677; P<0.001] and ALBI (HR 2.257; 95% CI: 1.528–3.333; P<0.001) scores were identified as the independent predictors in OS for HCC patients (Table 2).

Table 2

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | Child-Pugh model | ALBI model | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | Ref | |||||||

| Male | 1.255 (0.831–1.896) | 0.280 | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| ≥65 | 1.700 (1.134–2.528) | 0.009 | 1.840 (1.235–2.742) | 0.003 | 1.692 (1.137–2.517) | 0.009 | ||

| Tumor number | ||||||||

| Solitary | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Multiple | 1.852 (1.234–2.777) | 0.003 | 1.887 (1.257–2.833) | 0.002 | 1.850 (1.248–2.810) | 0.003 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||||

| <2 | Ref | |||||||

| ≥2 | 1.312 (0.878–1.962) | 0.185 | ||||||

| NLR | ||||||||

| ≤2 | Ref | |||||||

| >2 | 1.087 (0.741–1.594) | 0.668 | ||||||

| Creatine (μmol/L) | 1.002 (0.993–1.011) | 0.726 | ||||||

| AFP (ng/mL) | ||||||||

| <100 | Ref | |||||||

| ≥100 | 1.657 (1.083–2.534) | 0.020 | ||||||

| ALT (U/L) | ||||||||

| <40 | Ref | |||||||

| ≥40 | 0.689 (0.424–1.120) | 0.133 | ||||||

| Etiology of liver disease | ||||||||

| Other | Ref | |||||||

| HBV positive | 0.887 (0.546–1.442) | 0.629 | ||||||

| AST (U/L) | ||||||||

| <40 | Ref | |||||||

| ≥40 | 1.207 (0.799–1.823) | 0.371 | ||||||

| PLT (109/L) | ||||||||

| ≥100 | Ref | |||||||

| <100 | 1.734 (1.178–2.551) | 0.005 | ||||||

| GGT (U/L) | ||||||||

| <60 | Ref | |||||||

| ≥60 | 1.537 (1.049–2.251) | 0.027 | ||||||

| ALP (U/L) | ||||||||

| <125 | Ref | |||||||

| ≥125 | 1.647 (1.074–2.524) | 0.022 | ||||||

| Child-Pugh grade | ||||||||

| A | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| B | 2.305 (1.514–3.510) | <0.001 | 2.411 (1.581–3.677) | <0.001 | ||||

| ALBI grade | ||||||||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 2/3 | 2.290 (1.551–3.382) | <0.001 | 2.257 (1.528–3.333) | <0.001 | ||||

| ALB (g/L) | ||||||||

| ≥35 | Ref | |||||||

| <35 | 2.493 (1.671–3.718) | <0.001 | ||||||

| TBIL (μmol/L) | ||||||||

| ≤34 | Ref | |||||||

| >34 | 2.436 (1.499–3.958) | <0.001 | ||||||

OS, overall survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Ref, reference; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; NLR neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ALB, albumin; AST, aspartic transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PLT, platelet; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; TBIL, total bilirubin.

During RFS analysis, age, tumor number, tumor size, PLT, GGT, ALP and ALBI grade showed statistical significance while C-P grade exhibited no association with RFS. As suggested by Cox multivariate analysis, the independent risk factors for postoperative HCC recurrence included ALBI grade 2-3 [hazard ratio (HR) 1.536; 95% CI: 1.210–1.951; P<0.001], multiple tumors (HR 1.461; 95% CI: 1.109–1.924; P=0.007), tumor size ≥2 cm (HR 1.307; 95% CI: 1.0360–1.710; P=0.029), and age ≥65 years (HR 1.307; 95% CI: 1.002–1.704; P=0.048) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | Ref | ||||

| Male | 0.918 (0.694–1.214) | 0.548 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| <65 | Ref | Ref | |||

| ≥65 | 1.334 (1.024–1.737) | 0.032 | 1.307 (1.002–1.704) | 0.048 | |

| Tumor number | |||||

| Solitary | Ref | Ref | |||

| Multiple | 1.471 (1.118–1.936) | 0.006 | 1.461 (1.109–1.924) | 0.007 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||

| <2 | Ref | Ref | |||

| ≥2 | 1.335 (1.037–1.719) | 0.025 | 1.307 (1.036–1.710) | 0.029 | |

| Creatine (μmol/L) | 1.003 (0.997–1.008) | 0.329 | |||

| AFP (ng/mL) | |||||

| <100 | Ref | ||||

| ≥100 | 1.199 (0.895–1.606) | 0.224 | |||

| ALT (U/L) | |||||

| <40 | Ref | ||||

| ≥40 | 0.927 (0.696–1.235) | 0.604 | |||

| Etiology of liver disease | |||||

| Other | Ref | ||||

| HBV positive | 1.105 (0.752–1.367) | 0.923 | |||

| NLR | |||||

| ≤2 | Ref | ||||

| >2 | 1.016 (0.798–1.292) | 0.899 | |||

| AST (U/L) | |||||

| <40 | Ref | ||||

| ≥40 | 1.059 (0.808–1.388) | 0.678 | |||

| PLT (109/L) | |||||

| ≥100 | Ref | ||||

| <100 | 1.443 (1.136–1.833) | 0.003 | |||

| GGT (U/L) | |||||

| <60 | Ref | ||||

| ≥60 | 1.310 (1.023–1.678) | 0.032 | |||

| ALP (U/L) | |||||

| <125 | Ref | ||||

| ≥125 | 1.418 (1.070–1.878) | 0.015 | |||

| Child-Pugh grade | |||||

| A | Ref | ||||

| B | 1.128 (0.819–1.553) | 0.461 | |||

| ALBI grade | |||||

| 1 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2/3 | 1.543 (1.216–1.957) | <0.001 | 1.536 (1.210–1.951) | <0.001 | |

| ALB (g/L) | |||||

| ≥35 | Ref | ||||

| <35 | 1.454 (1.089–1.940) | 0.011 | |||

| TBIL (μmol/L) | |||||

| ≤34 | Ref | ||||

| >34 | 1.216 (0.827–1.787) | 0.321 | |||

RFS, recurrence-free survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; Ref, reference; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBV, hepatitis B virus; PLT, platelet; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ALB, albumin; TBIL, total bilirubin; AST, aspartic transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.

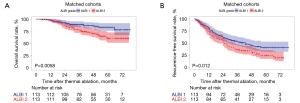

PSM based on C-P A patients

A contrast of the base line clinical and lab variables in the original cohort was performed to reveal that a significantly larger number of patients in the ALBI-1 group exhibiting higher PLT level, lower AST level, lower GGT level and lower ALP level than those in the ALBI-2 group (Table 4; all P values <0.05). The PSM procedure (1:1 matching) was followed to obtain 2 new cohorts of 113 and 113 sufferers in the ALBI-1 and ALBI-2 groups, separately. The entire variates were found to be well balanced following PSM adjustment. As shown in Table 4, P value invariably exceeds 0.05. After PSM, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates reached 93.8%, 86.2%, and 78.1% in the ALBI-1 group as well as 87.6%, 70.8%, and 60.0% in the ALBI-2 group, respectively (P=0.0058), as shown in Figure 3A. After PSM, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates reached 63.7%, 46.1%, and 40.4% in the ALBI 1 group as well as 57.5%, 33.9%, and 19.4% in the ALBI 2 group, respectively (P=0.012) (Figure 3B).

Table 4

| Variable | Child-Pugh A patients | Propensity-score-matched cohort (1:1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALBI-1 [246] | ALBI-2 [152] | P value | ALBI-1 [113] | ALBI-2 [113] | P value | ||

| Male (%) | 196 (79.7) | 108 (71.1) | 0.065 | 83 (73.5) | 81 (71.7) | 0.881 | |

| Age (years) | 58.11 (8.30) | 59.45 (8.81) | 0.128 | 59.33 (7.83) | 58.48 (9.20) | 0.455 | |

| Tumor number (%) | 0.655 | 0.985 | |||||

| 1 | 196 (79.7) | 119 (78.3) | 87 (77.0) | 88 (77.9) | |||

| 2 | 39 (15.9) | 23 (15.1) | 21 (18.6) | 20 (17.7) | |||

| 3 | 11 (4.5) | 10 (6.6) | 5 (4.4) | 5 (4.4) | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.47 (0.82) | 2.32 (0.76) | 0.061 | 2.40 (0.81) | 2.36 (0.76) | 0.684 | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 116.51 (321.84) | 116.39 (278.06) | 0.997 | 137.91 (407.75) | 121.28 (300.49) | 0.727 | |

| HBV/HCV infection (%) | 229 (93.1) | 98 (93.4) | 1.000 | 105 (92.9) | 106 (93.8) | 1.000 | |

| PLT (×109/L) | 129.17 (55.36) | 94.31 (61.72) | <0.001 | 97.16 (41.48) | 94.04 (52.71) | 0.621 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.24 (37.49) | 35.85 (25.25) | 0.640 | 34.27 (27.97) | 32.95 (21.90) | 0.692 | |

| AST (U/L) | 33.09 (25.71) | 40.66 (25.09) | 0.004 | 35.57 (23.65) | 36.67 (20.39) | 0.707 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 86.44 (30.73) | 104.93 (45.89) | <0.001 | 96.39 (35.69) | 92.06 (30.33) | 0.327 | |

| GGT (U/L) | 58.61 (82.88) | 87.85 (143.63) | 0.010 | 76.22 (103.99) | 64.95 (73.56) | 0.348 | |

| NLR | 2.62 (1.50) | 2.52 (1.71) | 0.574 | 2.70 (1.38) | 2.62 (1.81) | 0.688 | |

| Creatine (μmol/L) | 69.41 (16.71) | 65.33 (26.50) | 0.060 | 67.47 (17.94) | 66.94 (29.74) | 0.871 | |

PSM, propensity-score matching; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PLT, platelet; AST, aspartic transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; NLR neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.

Discussion

In this study, an assessment was conducted of ALBI grade for its effectiveness in evaluating the prognosis of early-stage HCC patients treated with thermal ablation. ALBI grade was identified as an independent factor in both OS and RFS while Child-Pugh grade demonstrated splendid discrimination power during the evaluation of OS sufferers with HCC posterior to thermal ablation rather than the assessment of tumor recurrence. Moreover, the ALBI gradation was applicable to categorize the sufferers with C-P A into two different prognostic cohorts after PSM. Our findings are consistent with the previous findings that ALBI can be used as biomarker for stratifying the prognosis of HCC patients.

C-P has been extensively utilized as a prognosis tool for those sufferers with hepatic illnesses to improve hepatic functions and alleviate portal hypertension. Unfortunately, the use of C-P fails to bring down mortality among those patients on the liver transplantation list. There are some issues worth noting with regard to C-P grade (20). With the emergence of more accurate tools, there have been some scholars proposing to find substitute to Child-Pugh in some particular circumstances. First established to assess HCC patients for their liver function, ALBI is now applied to predict the prognosis of those patients suffering acute or chronic liver failure, it is worth mentioning such advantages as the ease to obtain variables and the simplicity of calculation (21,22). In a largescale, multi-center research finished by Pinato et al. (9), it was corroborated that the ALBI gradation displayed its significance in making prediction for those HCC sufferers in multiple Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer system phases. It was even discovered that when the ALBI gradation was adopted rather than the C-P scoring, the ALBI-derived Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system and the ALBI-derived Japanese Integrated Staging system demonstrated comparable or greater power in prognosis forecast in contrast to the C-P-derived systems (23,24). Some studies compared the forecast function of C-P and ALBI in speculating HCC relapse. Jaruvongvanich et al. found that ALBI was better than C-P in forecasting early relapse (8). Luo et al. recruited HBV-associated HCC sufferers receiving curative excision. ALBI exhibited better forecast capability in contrast to C-P of postoperation relapse (25). Xiao et al. believed that no significant differences in the C-P grade in terms of RFS analysis among patients underwent radical resection. However, the ALBI grade was the independent risk factor associated with tumor recurrence (26). Moreover, for sufferers with C-P A, which is the main inclusive standard for hepatic function in substantial RCTs, the prognoses show variations as well. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a novel evaluation tool which breaks the restrictions on C-P gradation as aforementioned for HCC, which is particularly significant for the study design of HCC-related RCTs (10).

Herein, the independent risky factors in OS and RFS were identified for those HCC patients undergoing thermal ablation in line with the Milan criteria. It was found out that older age, poorer liver function reserve (i.e., ALBI gradation and C-P gradation) and cancer factors (i.e., tumor size, tumor quantity and a-fetoprotein contents) were associated with poorer OS, which is consistent with previous findings (27). Despite no remarkable diversity identified between the ALBI gradation and the C-P gradation in OS, the ALBI grade demonstrated the ease of application and objectiveness, which makes it more suitable for large-scale multicenter or international studies. Furthermore, an analysis was conducted with regard to the independent risk factors associated with RFS, which led to the result that the size and number of tumor, serum AFP level, as well as total tumor size were correlated with a higher risk of recurrence after thermal ablation, which is consistent with the results obtained from the published studies of those HCC patients who underwent surgical resection (28). However, the Child-Pugh grade system failed the assessment of RFS. For this reason, our results also indicate the potential that ALBI grade is more effective in predicting disease recurrence after thermal ablation for HCC patients beyond Milan criteria. The anti-cancer effect of albumin can also help explain the correlation between a high ALBI gradation and a high rate of postoperation relapse (29). The low levels of serum albumin are a potential cause of the high ALBI grade. As suggested by Carr et al. (30), those patients with low levels of serum albumin displayed such features as larger cancer sizes, greater AFP contents, more cancers and elevated portal vein cancer thrombogenesis. According to Carr et al. (30), the reduction in serum albumin contents might be a contributor to the invasive ability of HCC. In a fundamental study, it was revealed that albumin directly exerted an effect on suppressing HCC growth (31). Given various risk factors, those patients who were aged over 65 and had high ALBI levels and multiple tumors deserve more particular attention from the physician.

Herein, it was demonstrated that the ALBI grade could be used to separately predict OS and RFS for those HCC patients who had Child-Pugh A and underwent thermal ablation. Following PSM, there was a remarkable diversity observed in OS and RFS between ALBI-1 gradation and ALBI-2 gradation. Due to the aforementioned advantages of ALBI grade and the significant survival heterogeneity among C-P A patients, ALBI grade can be applied as one of the inclusion criteria for the liver function assessment of HCC patients. Furthermore, the capability to identify those sub-groups with superior prognoses from within the C-P A group endows the ALBI gradation with a potential of use as an alternative method in RCTs, particularly for the thermal ablation as treatment of HCC.

There are some limitations on this study. First of all, there is a potential of introducing selection bias due to the design of our retrospective study. Secondly, since this is a single-center study, the results obtained in this study might not apply to other settings. Thirdly, compared with C-P A patients, the proportion of patients in C-P B is relatively low. Thus, the difference between C-P A and C-P B in RFS need to be validated by other research groups. Further large-scale studies are warranted to compare the prognoses among different C-P grades. Lastly, a vast majority of the patients in our cohort had HCC caused by HBV, which means our findings must be further verified for those patients with other etiologies.

In conclusion, for those HCC patients undergoing thermal ablation, our study reveals that ALBI level could be applied to assess liver function and more suitable for the assessment of prognosis than the C-P grade in RFS. Moreover, the patients with the C-P grade A could be divided into multiple subgroups with distinct survival according to ALBI grade in both OS and RFS. Such findings may play a significant role in the future design of research and improving its predictability. Thus, it is essential to tailor this high-quality, evidence-based model to the existing HCC staging process.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (CN) (No. 18JCYBJC26900) and the Tianjin Health Science and Technology Project (No. KJ20170). This article was funded by Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-244/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-244/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-244/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-22-244/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This is an observational study. The Tianjin Third Central Hospital Institutional Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018;391:1301-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruzzenente A, Guglielmi A, Sandri M, et al. Surgical resection versus local ablation for HCC on cirrhosis: results from a propensity case-matched study. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:301-11; discussion 311. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durand F, Valla D. Assessment of the prognosis of cirrhosis: Child-Pugh versus MELD. J Hepatol 2005;42:S100-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durand F, Valla D. Assessment of prognosis of cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis 2008;28:110-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:550-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hansmann J, Evers MJ, Bui JT, et al. Albumin-Bilirubin and Platelet-Albumin-Bilirubin Grades Accurately Predict Overall Survival in High-Risk Patients Undergoing Conventional Transarterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017;28:1224-1231.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaruvongvanich V, Sempokuya T, Wong L. Is there an optimal staging system or liver reserve model that can predict outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma? J Gastrointest Oncol 2018;9:750-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Allara E, et al. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017;66:338-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edeline J, Blanc JF, Johnson P, et al. A multicentre comparison between Child Pugh and Albumin-Bilirubin scores in patients treated with sorafenib for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Int 2016;36:1821-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kudo M, et al. Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) Grade as Part of the Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for HCC of the Japan Society of Hepatology: A Comparison with the Liver Damage and Child-Pugh Classifications. Liver Cancer 2017;6:204-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee IC, Hung YW, Liu CA, et al. A new ALBI-based model to predict survival after transarterial chemoembolization for BCLC stage B hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int 2019;39:1704-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray LJ, Sykes J, Brierley J, et al. Baseline Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) Score in Western Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated With Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018;101:900-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, et al. Impact of albumin-bilirubin grade on survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who received sorafenib: An analysis using time-dependent receiver operating characteristic. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34:1066-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruix J, Sherman MPractice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005;42:1208-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ding J, Jing X, Wang Y, et al. Thermal ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale analysis of long-term outcome and prognostic factors. Clin Radiol 2016;71:1270-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ding J, Zhou Y, Wang Y, et al. Percutaneous microwave ablation of exophytic tumours in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: Safe or not? Liver Int 2017;37:1365-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara S, Chiba T, Ooka Y, et al. Liver function assessment according to the Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) grade in sorafenib-treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest New Drugs 2015;33:1257-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman RB Jr, Edwards EB. Liver transplant waiting time does not correlate with waiting list mortality: implications for liver allocation policy. Liver Transpl 2000;6:543-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen B, Lin S. Albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score at admission predicts possible outcomes in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7142. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng Y, Qi X, Tang S, et al. Child-Pugh, MELD, and ALBI scores for predicting the in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;10:971-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan AW, Chong CC, Mo FK, et al. Applicability of albumin-bilirubin-based Japan integrated staging score in hepatitis B-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:1766-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Michitaka K, et al. Usefulness of albumin-bilirubin grade for evaluation of prognosis of 2584 Japanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:1031-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luo HM, Zhao SZ, Li C, et al. Preoperative platelet-albumin-bilirubin grades predict the prognosis of patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0226. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiao H, Li JL, Chen SL, et al. A Pre-Operative Prognostic Score for Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Who Underwent Resection. Front Oncol 2021;11:569515. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- An C, Li X, Yu X, et al. Nomogram based on albumin-bilirubin grade to predict outcome of the patients with hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after microwave ablation. Cancer Biol Med 2019;16:797-810. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ho SY, Hsu CY, Liu PH, et al. Albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade-based nomogram to predict tumor recurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:776-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Luo Y, Li C, et al. The combination of the preoperative albumin-bilirubin grade and the fibrosis-4 index predicts the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. Biosci Trends 2019;13:351-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr BI, Guerra V. Serum albumin levels in relation to tumor parameters in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Biol Markers 2017;32:e391-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bağırsakçı E, Şahin E, Atabey N, et al. Role of Albumin in Growth Inhibition in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncology 2017;93:136-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]