Expanding treatment options for metastatic gastric cancer

Li et al. published a clinical study evaluating the efficacy and safety of Apatinib (a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) versus placebo in the treatment of patients with gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma for whom at least two lines of prior chemotherapy had failed (1).

This is a randomised, double-blind study performed in 32 centers in China. A total of 273 patients were randomly assigned to apatinib or placebo. Apatinib showed to significantly improve the overall survival with an acceptable safety profile. In fact, the median survival was significantly improved in the Apatinib arm compared with the placebo (6.5 vs. 4.7 months; hazard ratio: 0.709). With regard to other efficacy end points, the median progression free survival was 2.6 months for the apatinib arm and 1.8 months for the placebo arm with a hazard ratio of 0.444. Finally, the proportion of patients who reported an objective response was 2.8% in patients treated with apatinib versus 0% in the placebo group and patients who reported a disease control rate was 42.1% in the apatinib group versus 8.8% in the placebo group. Quality of life determined using the European organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC; QLQ-C30) showed that was no significant differences between the two groups. In regard to adverse events, apatinib was generally well tolerated; the main reasons for dose reduction were hand-foot syndrome, proteinuria, and hypertension with about the 20% of patients who modified the dose of apatinib for side effects. Although, there is an imbalance in the percentage of patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 in favor of the apatinib arm (27.3%) compared with placebo arm (16.5%), no statistically significant difference was observed between the patient’s characteristics of the two arms.

Metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer is a lethal disease characterized by a very short overall survival, underlining a critical need of new therapeutic options. Therefore, the prognosis of metastatic gastric cancer is still very poor with a median overall survival that not exceed the year (2). For metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer patients, chemotherapy, with platinum-based and fluoropyrimidine combination regimens is considered the mainstay of first line of treatment (3). Unfortunately, although several molecular targets have been investigated, only trastuzumab in the HER2-positive setting and ramucirumab led to a clinical improvement in the survival of metastatic patients (4). Trastuzumab is a humanized recombinant monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to the extracellular domain of HER2 that account for only the 20% of patients (4). Ramucirumab, a monoclonal antibody vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFR)-2 inhibitor, showed alone or in combination with paclitaxel, a benefit in efficacy and survival in patients with metastatic gastric cancer who progressed after a first-line chemotherapy (4). Several different targeted agents against different molecular pathway showed no advantage on survival (5). Therefore, there is an urgent need for further active treatments beyond second and further lines of chemotherapy in metastatic setting mainly because the number of patients suitable for a third-line of chemotherapy is growing (4). In this scenario, Li et al. proposed apatinib in a group of patients heavily pretreated; in fact more than the 30% of patients are progressed after 3 or more lines of therapy with a very low percentage of patients intolerant of second-line treatment. In addition, the 20% of patients are with >2 metastatic sites and peritoneal metastases that are widely considered negative prognostic factors. For these reasons and considering the very worst prognosis of metastatic gastric cancer and of the limitation of therapeutical options, the improvement in efficacy of apatinib is clinically relevant and may impact on the future prognosis of patients.

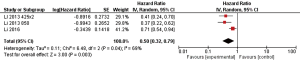

This is not the first clinical evidence of the efficacy of apatinib in gastric cancer. In fact, in 2010, a phase I study investigated the pharmacological activity and the maximum dose tolerable of apatinib for 34 patients with gastrointestinal tract cancer (6). Interestingly, the 7 patients achieving partial response were mainly with gastric cancer. In addition in 2013, a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer patients who do not respond to or who experience progression with second-line chemotherapy (7), showed an improvement of survival with apatinib versus placebo. Two different regimes of apatinib were investigated (850 mg once daily and 425 mg twice daily). The median overall survival values were 2.50 months in the placebo group and 4.83 and 4.27 months respectively in the apatinib group. The toxicity was low and easily manageable. A pooled analysis of both trials (Figure 1) showing that apatinib in third line of treatment in metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer was associated with a significant survival improvement with a cumulative hazard ratio of 0.50. A moderate heterogeneity between the two trials was observed in the interaction test.

Nonetheless, there are several open questions that should be assessed in the near future. (I) What is the efficacy of apatinib in previous lines of treatment? It is well known that first reports of another anti-VEGFR-2 therapy such as ramucirumab plus chemotherapy failed to show a progression free survival or overall survival advantage versus chemotherapy alone in front line of treatment (8). However, this is a small study with several bias in the selection of patients (4), and it is not possible to translate these negative results also for apatinib and therefore future trials are awaited to clarify the role of apatinib in previous lines of therapy (9); (II) is possible a combination of apatinib with other anti-neoplastic agents? We know that ramucirumab plus paclitaxel as second line treatment demonstrated a considerable superior activity (4); therefore it may be the same for apatinib; (III) is there a place for apatinib in maintenance therapy? For this question, several trials are launched and first results are awaited (9). Finally, we deem that in the near future, it will be more important to focus on the possible predictive biomarkers of response (such as VEGF; VEGFR2 expression) to help in selection of the optimal candidates to this novel therapy (10). In conclusion, although the evidences are small, apatinib seems one of the most promising agent for gastric or gastroesophageal junction carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned and reviewed by the Section Editor Fengbo Tan (Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2016.05.12). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial of Apatinib in Patients With Chemotherapy-Refractory Advanced or Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach or Gastroesophageal Junction. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1448-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petrioli R, Francini E, Roviello F, et al. Sequential treatment with epirubicin, oxaliplatin and 5FU (EOF) followed by docetaxel, oxaliplatin and 5FU (DOF) in patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal cancer: a single-institution experience. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015;75:941-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Haglund U, et al. Initial or delayed chemotherapy with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol 1994;5:189-90. [PubMed]

- Roviello G, Polom K, Petrioli R, et al. Monoclonal antibodies-based treatment in gastric cancer: current status and future perspectives. Tumour Biol 2016;37:127-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marano L, Chiari R, Fabozzi A, et al. c-Met targeting in advanced gastric cancer: An open challenge. Cancer Lett 2015;365:30-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zhao X, Chen L, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of novel selective vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibitor YN968D1 in patients with advanced malignancies. BMC Cancer 2010;10:529. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3219-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoon HH, Bendell JC, Braiteh FS, et al. Ramucirumab (RAM) plus FOLFOX as front-line therapy (Rx) for advanced gastric or esophageal adenocarcinoma (GE-AC): Randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase 2 trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:abstr 4004.

- Roviello G, Ravelli A, Polom K, et al. Apatinib: A novel receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of gastric cancer. Cancer Lett 2016;372:187-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roviello G, Petrioli R, Marano L, et al. Angiogenesis inhibitors in gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Gastric Cancer 2016;19:31-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]