Adjuvant therapy in early-stage small-cell lung cancer: what’s new?

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) represents approximately 15% of primary lung carcinomas. About 70% of patients are diagnosed as having extensive disease (ED) while in the other one third of patients, SCLC is diagnosed as limited disease (LD) (1). The prognosis of SCLC strongly depends on tumor stage. Staging of SCLC is traditionally based on the Veterans Administration Lung Study Group system, which classifies patients as having either LD [disease which is limited to one hemi-thorax, with hilar and mediastinal nodes that can be encompassed within one tolerable radiotherapy (RT) portal] or ED (when disease has progressed beyond any-type LD) (2). The new tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) version 7 staging system as adopted for non-small-cell lung cancer should also be used for SCLC. The current TNM staging system is based on 8,088 SCLC patients and provides better prognostic information and more precise nodal staging. In fact, LD stage includes T1–4, N0–3 M0 tumors, and in particular T1–2, N0–1 M0 tumors (previously described as ‘very limited stage’) were identified as a group with a more favorable outcome and represents about 5% of all new SCLC diagnosis (3).

Chemotherapy, mainly platinum-etoposide regimen, is the mainstay of the treatment in both LD- and ED-SCLC patients, while concurrent chemo-radiotherapy is the standard of care in healthy patients with LD-SCLC, regardless of the substage considered. Prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) should be offered to all patients who do not progress after induction therapy (4-6).

In the 1960s, surgery was considered a potential approach for LD-SCLC. Then, in a prospective trial, 144 LD-SCLC patients were randomized to surgery versus RT. At 10 years no survivors in the surgery arm were reported, but in the RT group 3 patients remained still alive and progression-free. The mean survival was 199 and 300 days (P=0.04), in the surgery and RT arm, respectively (7). The results of this trial, those showed by subsequent meta-analyses (8,9) and the fact that SCLC was characterized by a rapid doubling time, a propensity for early dissemination, significant sensitivity to chemotherapy and RT but with early development of drug resistance during the course of disease (10), led to the initial abandonment of surgery in the treatment of SCLC.

In the last few decades a renewed interest in surgery of very limited stage SCLC raised. Several studies demonstrated a 5-year survival rate of about 40–60% for stage I SCLC patients undergoing surgery (11-15). As result, all the main international guidelines now recommend surgery for clinical stage I SCLC patients (4-6).

Adjuvant chemotherapy, for pathologic stage I SCLC patients radically resected, has still not been evaluated in prospective randomized trials. Starting from 1980s–1990s, several reports suggested a benefit of chemotherapy after complete surgical resection (16-19). To the best of knowledge, to date there are only four single-arm prospective phase II trials evaluating the outcomes of patients who have undergone surgery with adjuvant therapy for LD-SCLC (20-23), no studies, either prospective or retrospective, have evaluated the role of adjuvant chemotherapy with thoracic RT.

A phase II study investigated the sequence of surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and etoposide) in 42 T1-3N0M0 SCLC patients. No thoracic or PCI was planned. The median survival was 32.7 months with a 5-year survival of 36%. In univariate and multivariate analyses, only the tumor stage (T1–2 versus T3) influenced survival (P<0.0001) (20). Another phase II study planned surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine) and thereafter by PCI in 183 T1-2N0M0 SCLC patients. The 30-month survival was 63% in 68 patients with T1N0M0R0-stages and 37% in 27 patients with T2N0M0R0-stages. The 4-year recurrence-free survival was 57% and 37%, respectively (21). A single arm trial enrolled 104 patients with early-stages SCLC. Fifty-one patients with clinical stages I or II SCLC received surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy and thoracic RT. Fifty-three patients with clinical stage III SCLC received induction chemotherapy followed by surgery and thoracic RT. Chemotherapy included three different regimens (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine; cisplatin, etoposide; cisplatin, etoposide, epirubicin) and 36 patients had PCI. In the overall population the median survival was 28 months with a 5-year survival rate of 32%. According to pathologic stages I, II and III the 5-year survival data were 52.2%, 30% and 15.3%, respectively (P<0.001) (22). A single-arm trial enrolled 62 patients who had complete-resection pathologic stage I, II, or IIIA SCLC receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin, etoposide). Overall 3-year survival was 61%. Median survival time was not reached in patients with pathologic stage I disease, it was 449 days in patients with stage II disease, and 712 days in patients with stage IIIA disease while the 3-year survival was 68%, 56%, and 13%, respectively (P=0.02). Loco-regional recurrence was more frequent in patients with stage IIIA disease. Distant failure and brain metastases were found in 34% and 15% of patients (23).

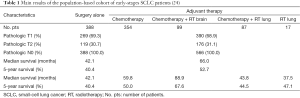

In April 2016, in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Chi-Fu Jeffrey Yang and colleagues (24) presented the results of the National Cancer Data Base analysis, from 2003 to 2011, to determine the potential benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy with and without PCI in early-stages SCLC patients who underwent complete resection. The primary endpoint was the overall survival of patients with pathologic T1-2N0M0 SCLC radically resected and stratified by adjuvant therapy approaches. Patients treated with induction therapy and those who died within 30 days of surgery were excluded from the analysis. Among 1,574 patients who underwent surgical resection for pathologic T1-2N0M0 SCLC, 954 patients (63.1%) were considered eligible for the analysis and 566 patients (59.3%) received adjuvant therapy after surgery. The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 43 months with a median survival of 55.6 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 49.1–62.7 months] and a 5-year survival rate of 47.4% (95% CI: 44.0–50.7%). The group of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation showed a significant increase in median survival with 66.0 months (95% CI: 56.8–79.3 months), compared with the group of patients who underwent surgery alone with a median survival of 42.1 months (95% CI: 34.0–51.8 months). The 5-year survival was 52.7% (95% CI: 48.2–57.0%) and 40.4% (95% CI: 35.2–45.5%), respectively (log-rank P<0.01). No significant differences in 5-year survival between patients who received radiation to the lung, with or without adjuvant chemotherapy, and patients who underwent surgery alone, were reported. The adjuvant chemotherapy alone or with PCI and lobectomy were significantly associated with improved survival rates whereas increasing age, tumor size, were associated with worse survival (Table 1).

Unfortunately, this study does not report the type of adjuvant chemotherapy regimen (i.e., platinum-based or not), the information on the specific type and anatomic target of adjuvant RT administered, due to the lack of this information in the analyzed database. It is not specified how many patients received radiation to both the lung and the brain because also these data are unlikely to be derived from the database. Moreover, the analysis of some adjuvant therapy groups (i.e., chemotherapy plus RT to the lung or/and to the brain; only RT to the lung) may have been underpowered as a result of sample size limitations, and further biases may have occurred. The Authors already underlined the limitations of their analysis which nevertheless does not lack interest. In fact, this study is the first population-based analyzing, although retrospectively, the impact of adjuvant therapy in resected T1–2N0M0 SCLC patients. The results are very interesting and in line with what already reported in literature by small phase II studies (20-23). The data of this retrospective analysis reinforced the endorsement of the main International guidelines which stated that for the treatment of patients with stage T1–2N0M0 SCLC underwent surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended (4-6).

The same authors reported the results of another population-based studies using the same National Cancer Data Base, from 2003 to 2011, but related to patients with clinical stage T1–2N0M0 SCLC. From a total of 4,729 patients who were treated for clinical T1–2N0M0 SCLC, using the propensity-score-matched analysis, the overall survival of 681 (14.4%) patients who underwent surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with or without RT versus 1,620 (34.3%) patients who received concurrent chemo-radiotherapy, was evaluated. Surgery was associated with a significantly higher survival than concurrent chemo-radiotherapy with the 5-year survival of 48.9% and 30.0%, respectively (log-rank P<0.001). Excluding from the analysis patients with comorbidities, a potential further bias, in the remaining 536 patients surgery remained significantly associated with a higher survival than concurrent chemo-radiotherapy with 5-year survival of 48.8% and 30.4%, respectively (log-rank P<0.01) (25).

Despite the lack of prospective randomized trials, the evidence coming from several studies recommend the multimodality approach for clinical and pathological T1–2N0M0 SCLC patients. In fact, in this very limited subgroup of patients, the reported results support an increased role of surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Platinum-etoposide, SCLC treatment standard of care regardless of stage, is the most appropriate regimen to use. The role of thoracic RT and PCI is still controversial. However, due to frequent early dissemination of SCLC, RT should be considered, too. Overall, notwithstanding the previous considerations, this recommendation comes from limited data (small phase II studies or retrospective analyses); the role of adjuvant therapy for T1–2N0M0 SCLC patient population is not yet well characterized and this subgroup should be the object of continued clinical study and randomized clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned and reviewed by the Section Editor Ke-Jun Liu (Department of Medical Oncology, Affiliated Dongguan People’s Hospital of Southern Medical University, Dongguan, China).

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2016.08.04). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4539-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel AM, Dunn WF, Trastek VF. Staging systems of lung cancer. Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68:475-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shepherd FA, Crowley J, Van Houtte P, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer lung cancer staging project: proposals regarding the clinical staging of small cell lung cancer in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the tumor, node, metastasis classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:1067-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Früh M, De Ruysscher D, Popat S, et al. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013;24:vi99-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jett JR, Schild SE, Kesler KA, et al. Treatment of small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e400S-19S.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Small Cell Lung Cancer (version 1.2016). Fort Washington, PA, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2016. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2016. Accessed on May 28, 2016. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sclc.pdf

- Fox W, Scadding JG. Medical Research Council comparative trial of surgery and radiotherapy for primary treatment of small-celled or oat-celled carcinoma of bronchus. Ten-year follow-up. Lancet 1973;2:63-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1618-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warde P, Payne D. Does thoracic irradiation improve survival and local control in limited-stage small-cell carcinoma of the lung? A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:890-5. [PubMed]

- Jackman DM, Johnson BE. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 2005;366:1385-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inoue M, Miyoshi S, Yasumitsu T, et al. Surgical results for small cell lung cancer based on the new TNM staging system. Thoracic Surgery Study Group of Osaka University, Osaka, Japan. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1615-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rostad H, Naalsund A, Jacobsen R, et al. Small cell lung cancer in Norway. Should more patients have been offered surgical therapy? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;26:782-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brock MV, Hooker CM, Syphard JE, et al. Surgical resection of limited disease small cell lung cancer in the new era of platinum chemotherapy: Its time has come. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:64-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim E, Belcher E, Yap YK, et al. The role of surgery in the treatment of limited disease small cell lung cancer: time to reevaluate. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1267-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schneider BJ, Saxena A, Downey RJ. Surgery for early-stage small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2011;9:1132-9. [PubMed]

- Karrer K, Shields TW, Denck H, et al. The importance of surgical and multimodality treatment for small cell bronchial carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1989;97:168-76. [PubMed]

- Merkle NM, Mickisch GH, Kayser K, et al. Surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986;34:39-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osterlind K, Hansen M, Hansen HH, et al. Influence of surgical resection prior to chemotherapy on the long-term results in small cell lung cancer. A study of 150 operable patients. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1986;22:589-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shepherd FA, Ginsberg RJ, Feld R, et al. Surgical treatment for limited small-cell lung cancer. The University of Toronto Lung Oncology Group experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:385-93. [PubMed]

- Macchiarini P, Hardin M, Basolo F, et al. Surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy for T1-3N0M0 small-cell lung cancer. Rationale for current approach. Am J Clin Oncol 1991;14:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karrer K, Ulsperger E. Surgery for cure followed by chemotherapy in small cell carcinoma of the lung. For the ISC-Lung Cancer Study Group. Acta Oncol 1995;34:899-906. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rea F, Callegaro D, Favaretto A, et al. Long term results of surgery and chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998;14:398-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya R, Suzuki K, Ichinose Y, et al. Phase II trial of postoperative adjuvant cisplatin and etoposide in patients with completely resected stage I-IIIa small cell lung cancer: the Japan Clinical Oncology Lung Cancer Study Group Trial (JCOG9101). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:977-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang CF, Chan DY, Speicher PJ, et al. Role of Adjuvant Therapy in a Population-Based Cohort of Patients With Early-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1057-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang CF, Chan DY, Yerokun B, et al. Surgery versus optimal medical management of early-stage small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:abstr 8511.