Prognostic value of primary tumor surgery in de novo stage IV breast cancer patients with different metastatic burdens: a propensity score-matched and population-based study

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed among women. In 2017, approximately 252,710 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 63,410 cases of in situ breast carcinoma were diagnosed in the United States (1). Overall, 5–9% of these patients were diagnosed with de novo stage IV breast cancer, which has a 10-year overall survival (OS) rate of approximately 13% (2). The current standard treatment for de novo stage IV breast cancer patients is systemic therapy, including endocrine therapy, anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) therapy and chemotherapy. However, the benefits of initial surgical treatment of the primary tumor for these patients remain unclear. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the performance of local breast surgery is reasonable in select patients who respond to initial systemic therapy (3).

A review of several retrospective studies on the prognostic value of primary site surgery showed that surgery could improve the median survival time by 1 year (4). However, a selection bias existed in the surgery group because patients with a younger age, smaller tumors, fewer comorbidities or a lower metastatic disease burden were more likely to be offered surgery (5,6). Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) focusing on this issue reported mixed results. Only the MF07-01 trial reported evidence supporting that primary site surgery could provide a 9-month OS benefit (7). Possible explanations for the inconsistent results among RCTs include heterogeneity among de novo stage IV breast cancer patients and selection bias.

Therefore, we aimed to evaluate an unbiased treatment effect of primary tumor surgery in de novo stage IV breast cancer patients in this study by implementing propensity score matching (PSM) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) and to explore the heterogeneity of treatment effects by subgroup analyses.

Methods

Database and patient characteristics

We conducted a retrospective case-control study of female patients diagnosed with de novo stage IV breast cancer between 2010 and 2015 in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database (SEER). This population was selected because it is the earliest cohort with complete records of HER2 status. The analysis was restricted to microscopically confirmed ductal, lobular and combined carcinoma (ICD-O-3: 8500-8543). Borderline estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2 statuses were defined as “unknown”. Patients with multiple primary cancers and those who underwent surgery at distant sites were excluded. Overall, 11,684 patients were eligible for this study and were classified as the training set.

Our study was approved by an independent ethical committee review board at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (Shanghai Cancer Center Ethical Committee).

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics were compared between patients who underwent surgery at the primary tumor site (the surgery group) and those who did not undergo surgery (the nonsurgery group) using Pearson’s χ2 test and the absolute standard difference. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to process predictors of primary tumor surgery.

To reduce the confounding bias of the baseline characteristics, we performed 1:1 PSM in the original cohort. The propensity score of the whole cohort was calculated by a multivariable logistic regression model using factors associated with surgery (multivariable logistic regression analysis P<0.05) or survival (multivariable Cox regression analysis P<0.05) as follows: age, race, marital status, tumor size, N stage, tumor grade, breast cancer subtype, number of metastases, and treatment. Nearest-neighbor matching without replacement was used to perform matching, and the caliper was set to 0.02. In addition, IPTW, a method based on propensity scoring used to balance baseline variables without loss of samples, was used to further reduce the impact of a selection bias. IPTW is regarded as a precise method that estimates treatment effects on time-to-event outcomes (8). Each patient was weighted by stabilized IPTW after the propensity score was generated, and stabilized IPTW was defined as previously described (9).

OS and breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) were compared between groups using the Kaplan-Meier method. A multivariate Cox regression model was used to determine the independent risk factors of BCSS and OS. Survival analyses of the IPTW-adjusted cohort were performed using the adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimator and log-rank test (10). The IPTW-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was calculated by multivariate Cox regression analyses to estimate the treatment effect in the IPTW-adjusted cohort.

Finally, we performed a subgroup analysis of patients with different metastatic patterns. Metastatic sites were defined according to bone, lung, liver and brain metastasis statuses as coded in the SEER database. The original cohort was divided into two subgroups: ≤2 metastatic sites and >2 metastatic sites. The baseline characteristics were rebalanced in the two groups by PSM, and the HR of surgery versus nonsurgery for each subtype was calculated to estimate the treatment effect in patients with different patterns of metastasis and tumor subtypes.

Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 3.3.4 (www.r-project.org). A two-sided P value less than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

Characteristics of de novo stage IV breast cancer patients and factors associated with surgery

We identified 11,684 de novo stage IV breast cancer patients, 3,730 (31.92%) of whom underwent surgery at the primary tumor site (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1. The patients who underwent surgery were younger, had more positive lymph nodes, were more frequently diagnosed with TNBC and had fewer metastatic sites. Regarding treatment, these patients were more likely to receive radiation combined with chemotherapy. The commonly used surgical procedures were modified radical mastectomy (1,707, 45.50%), breast-conserving surgery (1,091, 29.08%) and total mastectomy (823, 21.93%). Multivariate logistic regression revealed that age, tumor size, lymph node status, tumor grade, the number of metastases and treatment were associated with surgery selection (Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Original cohort | Logistic regression for primary surgery | PSM cohort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No surgery for the primary tumor (N=7,954), n (%) | Surgery for the primary tumor (N=3,730), n (%) | Pa | Odds ratio (surgery vs. nonsurgery) | Pb | No surgery for the primary tumor (N=3,063), n (%) | Surgery for the primary tumor (N=3,063), n (%) | Pa | |||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.716 | |||||||

| ≤55 years | 2,625 (33.0) | 1,634 (43.8) | Reference | 1,241 (40.5) | 1,256 (41.0) | |||||

| >55 years | 5,329 (67.0) | 2,096 (56.2) | 0.83 (0.76–0.91) | 1,822 (59.5) | 1,807 (59.0) | |||||

| Race | 0.143 | 0.772 | 0.421 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 5,917 (74.4) | 2,758 (73.9) | Reference | 2,266 (74.0) | 2,238 (73.1) | |||||

| African-American | 1,377 (17.3) | 638 (17.1) | 0.91 (0.80–1.02) | 542 (17.7) | 538 (17.6) | |||||

| Other | 624 (7.8) | 325 (8.7) | 0.94 (0.80–1.10) | 250 (8.2) | 278 (9.1) | |||||

| Unknown | 36 (0.5) | 9 (0.2) | 0.65 (0.27–1.41) | 5 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) | |||||

| Marital status | <0.001 | 0.014 | 0.793 | |||||||

| Married | 3,222 (40.5) | 1,779 (47.7) | Reference | 1,388 (45.3) | 1,368 (44.7) | |||||

| Other | 4,264 (53.6) | 1,752 (47.0) | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | 1,505 (49.1) | 1,515 (49.5) | |||||

| Unknown | 468 (5.9) | 199 (5.3) | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 170 (5.6) | 180 (5.9) | |||||

| Size | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.881 | |||||||

| ≤5 cm | 4,005 (50.4) | 2,163 (58.0) | Reference | 1,759 (57.4) | 1,740 (56.8) | |||||

| >5 cm | 2,246 (28.2) | 1,302 (34.9) | 0.88 (0.80–0.97) | 1,052 (34.3) | 1,065 (34.8) | |||||

| Unknown | 1,703 (21.4) | 265 (7.1) | 0.33 (0.28–0.38) | 252 (8.2) | 258 (8.4) | |||||

| N | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.607 | |||||||

| N0 | 1,815 (22.8) | 587 (15.7) | Reference | 567 (18.5) | 557 (18.2) | |||||

| N1 | 3,749 (47.1) | 1,435 (38.5) | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | 1,303 (42.5) | 1,336 (43.6) | |||||

| N2–N3 | 1,509 (19.0) | 1,606 (43.1) | 2.72 (2.39–3.09) | 1,075 (35.1) | 1,069 (34.9) | |||||

| Unknown | 881 (11.1) | 102 (2.7) | 0.52 (0.41–0.66) | 118 (3.9) | 101 (3.3) | |||||

| Tumor grade | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.801 | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 3,562 (44.8) | 1,410 (37.8) | Reference | 1,262 (41.2) | 1,239 (40.5) | |||||

| Grades 3–4 | 3,019 (38.0) | 2,093 (56.1) | 1.46 (1.33–1.61) | 1,575 (51.4) | 1,601 (52.3) | |||||

| Unknown | 1,373 (17.3) | 227 (6.1) | 0.50 (0.42–0.59) | 226 (7.4) | 223 (7.3) | |||||

| Subtypec | <0.001 | 0.187 | 0.95 | |||||||

| HR+/HER2− | 4,391 (55.2) | 1,884 (50.5) | Reference | 1,562 (51.0) | 1,543 (50.4) | |||||

| HR+/HER2+ | 1,298 (16.3) | 639 (17.1) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | 528 (17.2) | 541 (17.7) | |||||

| HR−/HER2+ | 670 (8.4) | 391 (10.5) | 1.00 (0.86–1.17) | 311 (10.2) | 324 (10.6) | |||||

| TNBC | 859 (10.8) | 604 (16.2) | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | 470 (15.3) | 459 (15.0) | |||||

| Unknown | 736 (9.3) | 212 (5.7) | 0.99 (0.82–1.18) | 192 (6.3) | 196 (6.4) | |||||

| Metastatic sites | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.656 | |||||||

| ≤2 | 6,012 (75.6) | 2,852 (76.5) | Reference | 2,405 (78.5) | 2,379 (77.7) | |||||

| >2 | 793 (10.0) | 128 (3.4) | 0.28 (0.22–0.34) | 116 (3.8) | 127 (4.1) | |||||

| Unknown/other metastatic sites | 1,149 (14.4) | 750 (20.1) | 1.41 (1.26–1.59) | 542 (17.7) | 557 (18.2) | |||||

| Treatment | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.587 | |||||||

| None | 2,950 (37.1) | 769 (20.6) | Reference | 723 (23.6) | 744 (24.3) | |||||

| Radiation | 1,048 (13.2) | 368 (9.9) | 1.34 (1.15–1.56) | 353 (11.5) | 326 (10.6) | |||||

| Chemotherapyd | 2,929 (36.8) | 1,328 (35.6) | 1.36 (1.21–1.53) | 1,237 (40.4) | 1,218 (39.8) | |||||

| Radiation and chemotherapy | 1,027 (12.9) | 1,265 (33.9) | 3.82 (3.36–4.35) | 750 (24.5) | 775 (25.3) | |||||

a, the P value was assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test; b, the P value was assessed using the likelihood ratio test; c, HR positivity was defined based on estrogen receptor positivity or progestogen receptor positivity; d, chemotherapy coded in the SEER database included chemotherapy prior to and following surgery. PSM, propensity score matching; HR, hormone receptor; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Adjustment for baseline biases using PSM and IPTW

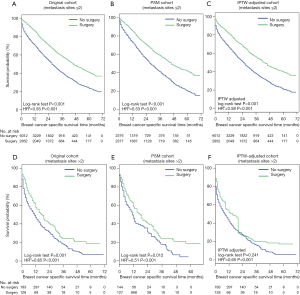

Significant differences among several baseline characteristics (Table 1, Pearson’s χ2 test P<0.05) and the absolute standard differences of several covariates were larger than 10% (Figure S1), indicating an imbalance in the demographic and clinicopathological characteristics between the surgery and nonsurgery groups. After PSM, 6,126 patients were successfully matched and were entered into subsequent analyses as the PSM cohort. Differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups were avoided (Table 1), and the absolute standard differences were <10% (Figure S1). After IPTW adjustment, the distributions of most demographic and clinicopathological characteristics were similar between the surgery and nonsurgery groups. The effect of the adjustment is depicted in Figure S1.

Clinical outcomes of primary tumor surgery

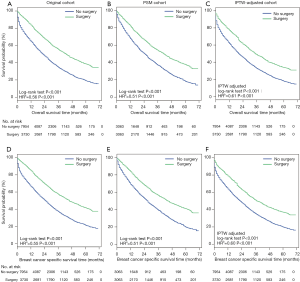

OS (Figure 2A,B,C) and BCSS (Figure 2D,E,F) were significantly longer in the surgery group in the original cohort, the PSM cohort and the IPTW-adjusted cohort. IPTW-adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves showed that the 5-year OS rate and the BCSS rate in the surgery group were significantly higher than those in the nonsurgery group [OS: 34.63% (95% CI: 28.57–40.68%) vs. 17.81% (95% CI: 12.01–23.62%); BCSS: 37.88% (95% CI: 31.7–44.05%) vs. 19.91% (95% CI: 13.85–25.97%)]. Similar results were observed in the original and PSM cohorts; the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates are listed in Table S1.

The multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that primary tumor surgery was associated with significant benefits for OS and BCSS after adjustment by IPTW (Table S2, IPTW-adjusted HR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.58–0.64; 0.60, 95% CI: 0.57–0.64 for OS and BCSS, respectively). Cox regression analysis in the original cohort and PSM cohort revealed a similar result (Table S2). Additionally, other variables associated with decreased OS and BCSS included age over 55 years, African-American, tumor size greater than 5 cm, tumor grades 2–3, the TNBC subtype, and more than 2 metastatic sites.

Subgroup analysis

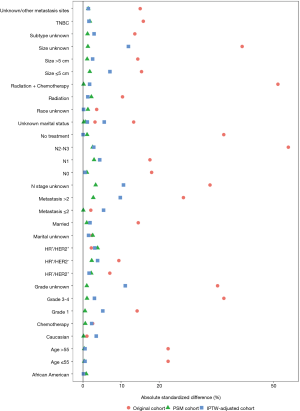

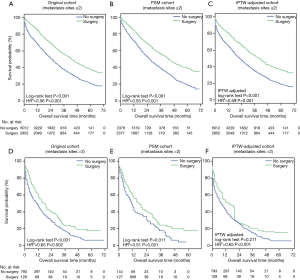

Three cohorts were stratified into two subgroups according to the number of metastases. Survival analysis in the subgroup with ≤2 metastatic sites showed that primary tumor surgery can provide significant benefits for OS (Figure S2A,B,C) and BCSS (Figure 3A,B,C) after PSM and IPTW adjustment. In the subgroup with >2 metastatic sites (Figure 3D,E,F), no significant difference in BCSS was observed according to the IPTW-adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 3F, IPTW adjusted P=0.241), but surgery was an independent factor associated with better survival according to IPTW-adjusted multivariate Cox regression (Figure 3F, IPTW-adjusted HR =0.65, P<0.001). Similar results with respect to OS were observed as shown in Figure S2.

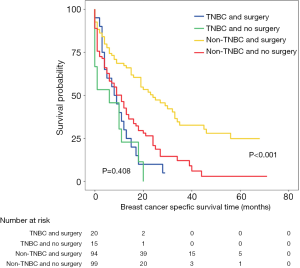

Furthermore, PSM was performed for the two subgroups, which further eliminated differences in baseline characteristics (Table S3). The subgroup analysis showed that patients with all subtypes and no more than 2 metastatic sites could achieve better outcomes through primary tumor surgery (Figure 4A,B, lower panel). Hormone receptor (HR)+/HER2− and TNBC patients with more than 2 metastatic sites who underwent primary tumor surgery exhibited no survival difference before PSM (Figure 4A,B, upper panel). Only the TNBC group was validated by PSM as a potential population that may not benefit from primary site surgery (Figure 4A,B, upper panel, Figure S3).

Discussion

A consensus regarding the role of primary site surgery in de novo stage IV breast cancer patients has not yet been reached. This study is one of the largest bias-controlled studies to evaluate the prognostic value of primary site surgery in this population. Even after adjusting for favorable baseline characteristics, surgery was still an independent factor associated with better survival in the whole population.

PSM and IPTW were performed in our study to obtain comparable baseline characteristics. Numerous retrospective studies have demonstrated the benefits of primary site surgery in stage IV breast cancer patients, although various confounding factors may contribute to biases between surgery and the nonsurgery groups (4,11-14). Patients with a better systemic condition may be more likely to undergo surgery at the primary site, while those with multiple distal metastases often fail to meet the criteria for surgery. PSM was performed in a published population-based analysis, but ER status, PR status and regional lymph node status were considered during PSM (13). Therefore, stricter PSM was performed in our study. Patients were matched if they shared a similar age, marital status, race, tumor size, lymph node status, tumor grade, subtype, number of metastases and treatments. Although we lost 5,558 patients after PSM, those who remained were well balanced, providing a solid basis for subsequent analyses. In addition, IPTW in all patients was proposed to estimate the treatment effect and therefore served as validation of PSM.

Several potential rationales exist for primary tumor resection in metastatic breast cancer. One hypothesis is that the effect of systemic therapy may be enhanced by a reduction in the tumor burden and nonvascularized regions that are inaccessible to drugs. Furthermore, circulating tumor cells have been confirmed to be strongly correlated with the prognosis of metastatic breast cancer patients (15). Circulating tumor cells have also been shown to disseminate from the primary tumor (16,17), and resection of the primary tumor may reduce the level of circulating tumor cells. Removal of the primary tumor provided a significant survival benefit in melanoma (18), renal-cell carcinoma (19,20), and colorectal cancer (21). This evidence from other tumor types provides proof that control of the primary tumor may prolong survival despite distant metastases.

Our study demonstrated that surgery for the primary tumor was associated with a better prognosis in de novo stage IV breast cancer patients. The reported survival rates of the patients who underwent primary site surgery in this study (Table S1) are comparable to those in the published literature (4,13). This conclusion is consistent with the results of the MF07-01 study, which enrolled 274 de novo stage IV patients who were randomized to the initial locoregional therapy plus systemic therapy group or the systemic therapy only group (7). Although the number of patients in the MF07-01 study may be slightly underestimated, positive results were still obtained. In contrast, the TATA trial and the TBCRC 013 trial, which only included patients who responded to chemotherapy, reported negative results (22,23). However, most HER2-positive patients in the TATA trial were not treated with anti-HER2 therapy, which is not consistent with current clinical practice. Two additional trials, ECOG2018 (NCT01242800) and JCOG1017 (UMIN000005586), are currently recruiting patients, both of which aim to clarify the effectiveness of primary tumor surgery for stage IV patients who are sensitive to systemic therapy. Similar to the MF07-01 trial, the POSYTIVE trial aimed to evaluate the effect of immediate surgery to remove the primary tumor in de novo stage IV breast cancer patients, but this trial obtained negative results and was terminated early due to poor recruitment (24).

Inconsistent results from current RCTs suggest that the heterogeneity among patients receiving surgery has not been clarified. The traditional view of metastatic breast cancer is that it is a systematic disease and local control has a limited impact on survival. As improved systemic therapies significantly prolong the survival of de novo stage IV breast cancer patients, local control plays a minor role in this population (25). Although the proportion of de novo stage IV breast cancer patients receiving primary site surgery decreased, the survival benefit in the surgery group increased over time (13,26), which may be partly due to the increasing detection rate of oligometastatic lesions in recent years via advanced imaging technology such as PET-CT. Thus, in this study, the prognostic value of surgery was evaluated in patients with different metastatic burdens.

The results showed that patients with more than 2 metastatic sites benefitted less from surgery than those with 1 or 2 sites. Kaplan-Meier curves showed that the survival difference was rather narrow after matching and was even non-significant after IPTW adjustment, but after multivariate Cox regression adjustment of confounding factors, primary tumor surgery was significantly associated with better survival in patients with a high metastatic burden (>2 metastatic sites). These results indicate substantial heterogeneity among patients with more than 2 metastatic sites. This result is in agreement with that of the MF07-01 trial in which the solitary bone metastasis subgroup showed significant survival benefits (7). Several retrospective studies demonstrated that patients with a lower metastatic burden may be potential candidates for surgery (12,27). Two meta-analyses showed that patients with fewer metastases could achieve a substantial benefit from surgery (6,28). A matched-pair study demonstrated no statistically significant improvement as a result of surgery in patients with visceral metastatic disease, and only patients with bone metastasis had improved survival if they received chemotherapy prior to primary site surgery (29).

To explore the heterogeneity among different metastatic burdens, further subgroup analyses were performed. The results demonstrated that TNBC was the only subtype that may not benefit from surgery. TNBC is an aggressive subtype of breast cancer characterized by extensive visceral metastasis and early recurrence between the first and third year after diagnosis (30,31). The 3-year OS rate of stage IV TNBC patients was reported to be 50% lower than that of non-TNBC patients (32). Different recurrence patterns among TNBC patients indicate that substantial heterogeneity existed among these patients. For those with high metastatic burdens at diagnosis, effective systemic therapy may be more important for highly aggressive TNBC.

Patients with hormone receptor-positive or HER2-positive disease achieved longer survival due to primary tumor surgery, while patients with TNBC did not benefit from surgery (33,34). However, another population-based SEER study found a conflicting result indicating that surgery could lead to better survival for all subtypes (35). Although no approaches were used to adjust for baseline characteristics, the baseline differences in the latter study were rather large. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first study to illustrate the survival outcomes of patients with any of the four molecular subtypes of de novo stage IV breast cancer with different metastatic burdens.

Inevitably, our study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, which may have introduced bias, but to control for bias as much as possible, we performed PSM and IPTW. Second, detailed information concerning chemotherapy, such as the types of chemotherapy regimens administered together with surgery, anti-HER2 therapy and endocrine therapy, was unknown, precluding control for these biases.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that resection of the primary tumor can significantly improve OS and BCSS in de novo stage IV breast cancer patients. Among patients with different metastatic burdens, those with more than two metastatic sites and TNBC may not be appropriate for surgery.

Table S1

| Variable | Year | Original cohort | PSM cohort | IPTW adjusted cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | No surgery | Surgery | No surgery | Surgery | No surgery | ||||

| OS | 1 | 83.58% (82.35–84.83%) | 64.47% (63.37–65.59%) | 82.57% (81.18–83.98%) | 68.46% (66.73–70.24%) | 77.94% (76.36–79.52%) | 61.67% (60.19–63.15%) | ||

| 3 | 55.21% (53.36–57.13%) | 34.53% (33.22–35.89%) | 54.92% (52.89–57.04%) | 36.86% (34.72–39.13%) | 49.87% (46.88–52.86%) | 32.78% (30.06–35.5%) | |||

| 5 | 38.55% (36.26–41.00%) | 19.01% (17.46–20.69%) | 39.19% (36.69–41.85%) | 18.21% (15.7–21.14%) | 34.63% (28.57–40.68%) | 17.81% (12.01–23.62%) | |||

| BCSS | 1 | 84.96% (83.77–86.18%) | 66.58% (65.49–67.69%) | 84.15% (82.81–85.52%) | 70.07% (68.35–71.83%) | 79.64% (78.1–81.17%) | 63.83% (62.36–65.29%) | ||

| 3 | 57.35% (55.49–59.28%) | 37.16% (35.79–38.58%) | 57.22% (55.16–59.35%) | 38.83% (36.63–41.17%) | 52.2% (49.21–55.19%) | 35.28% (32.51–38.04%) | |||

| 5 | 41.63% (39.25–44.14%) | 21.31% (19.65–23.12%) | 42.38% (39.81–45.12%) | 19.68% (16.99–22.78%) | 37.88% (31.7–44.05%) | 19.91% (13.85–25.97%) | |||

OS, overall survival; BCSS, breast cancer specific survival; PSM, propensity score matching; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weight.

Table S2

| Variable | OS | BCSS | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original cohort | PSM cohort | IPTW–adjusted cohort | Original cohort | PSM cohort | IPTW–adjusted cohort | ||||||||||||

| Hazard ratio | Pa | Hazard ratio | Pa | Hazard ratio | Pa | Hazard ratio | Pa | Hazard ratio | Pa | Hazard ratio | Pa | ||||||

| Primary site surgery | |||||||||||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| Yes | 0.56 (0.53–0.60) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.48–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.58–0.64) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.51–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.47–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.57–0.64) | <0.001 | |||||

| Age | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤55 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| >55 years | 1.38 (1.31–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.27–1.49) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.34–1.50) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.21–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.30–1.46) | <0.001 | |||||

| Race | |||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| African American | 1.19 (1.11–1.27) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.11–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.1–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.08–1.32) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.10–1.26) | <0.001 | |||||

| Other | 0.92 (0.83–1.02) | 0.121 | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) | 0.406 | 0.90 (0.81–0.99) | 0.029 | 0.94 (0.85–1.05) | 0.267 | 0.98 (0.85–1.12) | 0.737 | 0.92 (0.83–1.01) | 0.086 | |||||

| Marital status | |||||||||||||||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| Other | 1.26 (1.19–1.33) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.22–1.42) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) | <0.001 | 1.24 (1.17–1.31) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.15–1.28) | <0.001 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 0.104 | 1.28 (1.09–1.50) | 0.003 | 1.07 (0.95–1.19) | 0.260 | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) | 0.191 | 1.29 (1.09–1.52) | 0.003 | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) | 0.320 | |||||

| Size | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤5 cm | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| >5 cm | 1.20 (1.13–1.28) | <0.001 | 1.27 (1.17–1.37) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.14–1.28) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.18–1.40) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.15–1.30) | <0.001 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.28 (1.19–1.37) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.19–1.54) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.24–1.42) | <0.001 | 1.30 (1.21–1.40) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.22–1.59) | <0.001 | 1.36 (1.27–1.47) | <0.001 | |||||

| N | |||||||||||||||||

| N0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| N1 | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | 0.001 | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.026 | 0.87 (0.81–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.84–0.97) | 0.006 | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 0.032 | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | 0.001 | |||||

| N2–N3 | 0.98 (0.90–1.05) | 0.530 | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.153 | 0.91 (0.85–0.99) | 0.019 | 1.00 (0.93–1.09) | 0.936 | 0.93 (0.83–1.03) | 0.176 | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | 0.061 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.19 (1.08–1.31) | 0.001 | 1.22 (1.00–1.47) | 0.047 | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | 0.048 | 1.18 (1.06–1.3) | 0.002 | 1.18 (0.97–1.45) | 0.105 | 1.11 (1.01–1.23) | 0.037 | |||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||||||||||||

| Grade 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| Grade 3–4 | 1.47 (1.38–1.56) | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.40–1.66) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.40–1.58) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.35–1.53) | <0.001 | 1.54 (1.41–1.69) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.42–1.61) | <0.001 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.11 (1.02–1.20) | 0.013 | 1.19 (1.03–1.39) | 0.021 | 1.16 (1.07–1.25) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | 0.005 | 1.21 (1.04–1.41) | 0.016 | 1.18 (1.09–1.28) | <0.001 | |||||

| Subtypeb | |||||||||||||||||

| HR+/HER2− | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| HR+/HER2+ | 0.90 (0.82–0.97) | 0.009 | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.80–0.94) | 0.001 | 0.88 (0.81–0.96) | 0.005 | 0.75 (0.66–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.80–0.95) | 0.002 | |||||

| HR−/HER2+ | 1.18 (1.06–1.30) | 0.002 | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 0.614 | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) | 0.007 | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | 0.159 | 1.01 (0.87–1.18) | 0.858 | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | 0.013 | |||||

| TNBC | 2.82 (2.61–3.06) | <0.001 | 2.82 (2.54–3.14) | <0.001 | 2.81 (2.60–3.03) | <0.001 | 2.62 (2.41–2.84) | <0.001 | 2.88 (2.58–3.21) | <0.001 | 2.85 (2.63–3.09) | <0.001 | |||||

| Unknown | 1.44 (1.32–1.58) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.20–1.58) | <0.001 | 1.51 (1.39–1.65) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.33–1.59) | <0.001 | 1.38 (1.19–1.59) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.42–1.70) | <0.001 | |||||

| Metastasis number | |||||||||||||||||

| ≤2 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| >2 | 2.18 (2.00–2.37) | <0.001 | 2.40 (2.06–2.79) | <0.001 | 2.19 (2.01–2.38) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.63–1.85) | <0.001 | 2.54 (2.18–2.96) | <0.001 | 2.28 (2.10–2.49) | <0.001 | |||||

| Unknown/other metastasis sites | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) | 0.210 | 0.93 (0.85–1.03) | 0.162 | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.023 | 1.24 (1.14–1.35) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 0.143 | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | 0.041 | |||||

| Treatment | |||||||||||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 0.82 (0.75–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.67–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.82 (0.76–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 0.021 | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | 0.001 | 0.85 (0.78–0.92) | <0.001 | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.55 (0.51–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.48–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.51–0.58) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.51–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.50–0.62) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.52–0.60) | <0.001 | |||||

| Radiation + chemotherapy | 0.55 (0.51–0.60) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.45–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.54–0.63) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.56–0.66) | <0.001 | 0.52 (0.47–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.55–0.65) | <0.001 | |||||

a, P value was assessed using the Pearson’s χ2 test; b, HR positive means estrogen receptor positive or progestogen receptor positive. OS, overall survival; BCSS, breast cancer specific survival; PSM, propensity score matching; HR, hormone receptor; TNBC, triple negative breast cancer.

Table S3

| Characteristics | Metastasis number ≤2 after PSM | Metastasis number >2 after PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No surgery of primary tumor (n=2,373) | Surgery of primary tumor (n=2,373) | Pa | No surgery of primary tumor (n=114) | Surgery of primary tumor (n=114) | Pa | ||

| Age | 0.768 | 1.000 | |||||

| ≤55 years | 974 (41.0) | 985 (41.5) | 47 (41.2) | 47 (41.2) | |||

| >55 years | 1,399 (59.0) | 1,388 (58.5) | 67 (58.8) | 67 (58.8) | |||

| Race | 0.563 | 0.304 | |||||

| Caucasian | 1,075 (45.3) | 1,076 (45.3) | 36 (31.6) | 47 (41.2) | |||

| African American | 1,181 (49.8) | 1,164 (49.1) | 71 (62.3) | 60 (52.6) | |||

| Other | 117 (4.9) | 133 (5.6) | 7 (6.1) | 7 (6.1) | |||

| Unknown | 0.714 | 0.452 | |||||

| Marital status | 1,751 (73.8) | 1,730 (72.9) | 78 (68.4) | 85 (74.6) | |||

| Married | 434 (18.3) | 433 (18.2) | 23 (20.2) | 21 (18.4) | |||

| Other | 185 (7.8) | 207 (8.7) | 13 (11.4) | 8 (7.0) | |||

| Unknown | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Size | 0.648 | 0.863 | |||||

| ≤5 cm | 1,360 (57.3) | 1,387 (58.4) | 53 (46.5) | 56 (49.1) | |||

| >5 cm | 832 (35.1) | 818 (34.5) | 47 (41.2) | 43 (37.7) | |||

| Unknown | 181 (7.6) | 168 (7.1) | 14 (12.3) | 15 (13.2) | |||

| N | 0.430 | 0.784 | |||||

| N0 | 469 (19.8) | 467 (19.7) | 21 (18.4) | 22 (19.3) | |||

| N1 | 978 (41.2) | 1,027 (43.3) | 42 (36.8) | 44 (38.6) | |||

| N2–N3 | 842 (35.5) | 806 (34.0) | 45 (39.5) | 45 (39.5) | |||

| Unknown | 84 (3.5) | 73 (3.1) | 6 (5.3) | 3 (2.6) | |||

| Tumor grade | 0.431 | 0.591 | |||||

| Grade 1 | 1,010 (42.6) | 969 (40.8) | 30 (26.3) | 37 (32.5) | |||

| Grade 3–4 | 1,176 (49.6) | 1,220 (51.4) | 77 (67.5) | 71 (62.3) | |||

| Unknown | 187 (7.9) | 184 (7.8) | 7 (6.1) | 6 (5.3) | |||

| Subtypeb | 0.463 | 0.797 | |||||

| HR+/HER2− | 1,254 (52.8) | 1,251 (52.7) | 51 (44.7) | 45 (39.5) | |||

| HR+/HER2+ | 431 (18.2) | 395 (16.6) | 17 (14.9) | 21 (18.4) | |||

| HR−/HER2+ | 227 (9.6) | 223 (9.4) | 20 (17.5) | 18 (15.8) | |||

| TNBC | 333 (14.0) | 368 (15.5) | 15 (13.2) | 20 (17.5) | |||

| Unknown | 128 (5.4) | 136 (5.7) | 11 (9.6) | 10 (8.8) | |||

| Treatment | 0.558 | 0.390 | |||||

| None | 564 (23.8) | 558 (23.5) | 35 (30.7) | 29 (25.4) | |||

| Radiation | 292 (12.3) | 325 (13.7) | 3 (2.6) | 8 (7.0) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 916 (38.6) | 895 (37.7) | 34 (29.8) | 37 (32.5) | |||

| Radiation + chemotherapy | 601 (25.3) | 595 (25.1) | 42 (36.8) | 40 (35.1) | |||

a, P value was assessed using the Pearson’s χ2 test; b, HR positive means estrogen receptor positive or progestogen receptor positive. PSM, propensity score matching; HR, hormone receptor; TNBC, triple negative breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2019.03.21). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. This article was approved by an independent ethical committee review board at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (Shanghai Cancer Center Ethical Committee).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- DeSantis CE, Ma J, Sauer AG, et al. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2017, Racial Disparity in Mortality by State. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:439-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eng LG, Dawood S, Sopik V, et al. Ten-year survival in women with primary stage IV breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;160:145-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical prac- tice guidelines in oncology. Breast Cancer. 2018;1:2018.

- Blanchard DK, Shetty PB, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Association of surgery with improved survival in stage IV breast cancer patients. Ann Surg 2008;247:732-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan SA. Primary tumor resection in stage IV breast cancer: consistent benefit, or consistent bias? Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:3285-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harris E, Barry M, Kell MR. Meta-analysis to determine if surgical resection of the primary tumour in the setting of stage IV breast cancer impacts on survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:2828-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soran A, Ozmen V, Ozbas S, et al. Randomized Trial Comparing Resection of Primary Tumor with No Surgery in Stage IV Breast Cancer at Presentation: Protocol MF07-01. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:3141-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios. Stat Med 2013;32:2837-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:656-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimator and log‐rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat Med 2005;24:3089-110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Babiera GV, Rao R, Feng L, et al. Effect of primary tumor extirpation in breast cancer patients who present with stage IV disease and an intact primary tumor. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:776-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rapiti E, Verkooijen HM, Vlastos G, et al. Complete Excision of Primary Breast Tumor Improves Survival of Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer at Diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2743-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warschkow R, Guller U, Tarantino I, et al. Improved survival after primary tumor surgery in metastatic breast cancer a propensity-adjusted, population-based SEER trend analysis. Ann Surg 2016;263:1188-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas A, Khan SA, Chrischilles EA, et al. Initial Surgery and Survival in Stage IV Breast Cancer in the United States, 1988-2011. JAMA Surg 2016;151:424-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:781-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fehm T, Sagalowsky A, Clifford E, et al. Cytogenetic Evidence That Circulating Epithelial Cells in Patients with Carcinoma Are Malignant Advances in Brief Cytogenetic Evidence That Circulating Epithelial Cells in Patients with Carcinoma Are Malignant 1. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:2073-84. [PubMed]

- Budd GT, Cristofanilli M, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells versus imaging - Predicting overall survival in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:6403-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Essner R, Lee JH, Wanek LA, et al. Contemporary surgical treatment of advanced-stage melanoma. Arch Surg 2004;139:961-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1655-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mickisch GHJ, Garin A, Van Poppel H, et al. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;358:966-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen SA, Buell JF, Yoshida A, et al. Initial presentation with stage IV colorectal cancer: how aggressive should we be? Arch Surg 2000;135:530-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Badwe R, Hawaldar R, Nair N, et al. Locoregional treatment versus no treatment of the primary tumour in metastatic breast cancer: An open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1380-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tari K, Jaclyn L, Mithat G, et al. A prospective analysis of surgery and survival in stage IV breast cancer (TBCRC 013). J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1006. [Crossref]

- Fitzal F, Bjelic-Radisic V, Knauer M, et al. Impact of Breast Surgery in Primary Metastasized Breast Cancer: Outcomes of the Prospective Randomized Phase III ABCSG-28 POSYTIVE Trial. Ann Surg 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chia SK, Speers CH, D'Yachkova Y, et al. The impact of new chemotherapeutic and hormone agents on survival in a population-based cohort of women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer 2007;110:973-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas A, Khan SA, Chrischilles EA, et al. Initial surgery and survival in stage IV breast cancer in the United States, 1988-2011. JAMA Surg 2016;151:424-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barinoff J, Schmidt M, Schneeweiss A, et al. Primary metastatic breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy-prognostic impact and the role of breast tumour surgery. Eur J Cancer 2017;83:116-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petrelli F, Barni S. Surgery of primary tumors in stage IV breast cancer: an updated meta-analysis of published studies with meta-regression. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England) 2012;29:3282-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cady B, Nathan N, Michaelson J, et al. Matched pair analyses of stage IV breast cancer with or without resection of primary breast site. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:3384-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metzger-Filho O, Tutt A, de Azambuja E, et al. Dissecting the heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1879-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4429-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bagaria SP, Ray PS, Sim M-S, et al. Personalizing breast cancer staging by the inclusion of ER, PR, and HER2. JAMA surgery 2014;149:125-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neuman HB, Morrogh M, Gonen M, et al. Stage IV breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy: does surgery of the primary tumor matter? Cancer 2010;116:1226-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan Y, Li X, Chen H, et al. Hormone receptor status may impact the survival benefit of surgery in stage iv breast cancer: a population-based study. Oncotarget 2016;7:70991-1000. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu SG, Zhang WW, Sun JY, et al. The survival benefits of local surgery in stage IV breast cancer are not affected by breast cancer subtypes: a population-based analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8:67851. [PubMed]