Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer: state of the art

Introduction

EC is a common gynecologic malignancy with an increasing incidence and an age of onset younger than in prior years (1,2).

EC typically has a well or moderately differentiated endometrioid histotype at early-stages with a good prognosis. The surgical management for women with clinically apparent early-stage EC consists of total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with or without lymphadenectomy. The evaluation of lymph node status through pelvic and selective para-aortic node dissection is an invaluable prognostic factor for targeted adjuvant treatment (3).

Recently, it has been also discussed the role of intraoperative frozen section (FS) diagnosis during hysterectomy for early-stage EC to determine the depth of myometrial invasion and consequently to select the women to undergo lymphadenectomy. The Authors showed a concordance of FS and final pathology of 85.2%, with an under-diagnosis rate of 14%, over-diagnosis rate of 0.8%, and overall accuracy of FS in predicting myometrial invasion of 93.3% (4).

The role of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy is a controversial topic in the surgical treatment of these patients and there is a disagreement among clinical practices, with surgical approaches varying from no nodal evaluation to full lymphadenectomy (5-7).

A non-standardized surgical approach is explained by discordant data regarding the therapeutic value of systematic lymphadenectomy.

A retrospective study documented the positive effects of pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy on survival rates (8) whereas two randomized prospective European studies conflicted with these results (9,10) demonstrating no advantage in disease-free or overall survival. These trials were largely criticized in their study designs because included minimally invasive disease, limiting the ability to conclude.

Albeit the therapeutic role of lymphadenectomy is still questioned, its prognostic role is undoubted. Indeed prognosis of EC is correlated with lymph node status, which is itself related to the histologic grade, as well as the depth of myometrial invasion (11).

The patients with lymph node metastasis disease have significantly lower median survival rates in comparison to females with a tumor limited to the uterus: positive lymph node status restricts 5-year disease-free survival at stage 1 EC to 54% while it was 90% if the nodes were negative (12). In addition to the prognostic value, lymph node status assessment plays an essential role in tailoring adjuvant therapy.

The increasing awareness of some risks associated with lymphadenectomy, as intraoperative neurovascular injury and long-term complications such as leg lymphedema (13,14), called into question the benefit of the procedure in stage 1 where the incidence of lymph-node involvement is low. In the presence of G1 or G2 endometrioid EC and less than 50% myometrial invasion [Stage IA according to 2010 FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) staging)], the risk of lymph node metastasis is low. Conversely, in the case of G3 endometrioid EC or non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma (e.g., serous, clear cell carcinoma), independent of grade status, the risk of lymph node metastasis is high and an extended operative staging with lymphadenectomy is mandatory during surgery (4).

Chi et al. reported the incidence of pelvic nodal metastasis in patients classified as Stage I (2010 FIGO staging), concerning the grade of differentiation and depth of myometrial invasion. In this study, none of the 80 patients with grade 1 well-differentiated tumors had pelvic lymph node metastases irrespective of the depth of endometrial invasion. In patients with no myometrial invasion, only 2% (2/110) had nodal metastasis, which increased to 8% (13/64) for those with inner-half invasion and 20% (15/75) with outer half invasion (15).

Considered the low risk in early-stage disease of lymph-node metastases, performing a systematic lymphadenectomy may be more detrimental rather than helpful.

The purpose of this review is to give an overview of the sentinel lymph node (SLN) procedure in the management of patients affected by early-stage EC.

Material and methods

The data research was conducted using the following databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Sciences, Scopus, ClinicalTrial.gov, OVID and Cochrane Library querying for all articles related to SLN biopsy in the EC from the inception of the database up to December 2019. The studies were identified with the use of a combination of the following text words: endometrial cancer, systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy, SLN biopsy, indocyanine green (ICG), ultrastaging. The selection criteria of our narrative review included randomized clinical trials, non-randomized controlled studies (observational prospective, retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, case series) and review articles of the SLN biopsy in EC. A review of articles also included the abstracts of all references retrieved from the search. Article not in English language, conference papers and reviews, and studies with information overlapping another publication were excluded. In presence of overlapping studies, we took into account the most recent and/or most comprehensive manuscript.

Sentinel lymph-node mapping

The SLN mapping is a recent innovative method (16,17). This procedure permits the reduction of the morbidity associated with full lymphadenectomy without lacking prognostic information.

Besides, the minimally invasive laparoscopic hysterectomy approach with the combination of SLN biopsy constitutes an interesting alternative to contemporary surgical treatment particularly valuable in obese patients (16).

The use of SLN mapping is a well-known procedure in the treatment of melanoma (18) and breast cancer (19). It would seem to be useful in high-risk histologies, such as serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma (20). The purpose of using this tool is to target the lymph nodes that are the primary tumor drainage area and thus the most likely to metastasize. The pathologic exam of the SLN may with accuracy inform about the status of the regional lymphatic basin, thereby minimizing the risk of morbidity associated with a complete lymphadenectomy (21). It is precisely in the cases of the surgical staging of apparent uterine-confined malignancy when no metastasis is demonstrated by imaging studies or no obvious extrauterine disease at exploration, that the SLN mapping can be considered. In a recent meta-analysis, Bodurtha Smith et al. (22) presented data from 55 studies and 4,915 women. The overall detection rate of SLN mapping was 81% (95% CI, 77–84%) with a 50% bilateral pelvic node detection rate (95% CI, 44–56%) and 17% paraaortic detection rate (95% CI, 11–23%). The detection rate and accuracy of fluorescence-guided SLN mapping have been evaluated even in patients undergoing robotic-assisted surgery, as demonstrated in the pilot study of Paley et al. [2016]. At least one sentinel node was detected in 119/123 (96.7%) patients. Ninety-nine patients (80%) had bilateral pelvic and/or periaortic sentinel nodes successfully mapped. The final hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) examination revealed the presence of lymph node metastasis in only 10.6% of the patients undergoing completion lymphadenectomy. In 44% of these cases, interestingly, the sentinel node was the only positive node founded (isolated metastasis in SLN). The procedure showed a sensitivity of 100%: the examination of non-sentinel nodes (upon completion lymphadenectomy) revealed the absence of metastatic disease among cases where H&E of the sentinel node was negative. As expected, the specificity was 100% because no false-positive results occurred. All women affected by Stage IIIC disease were identified using SLN mapping (23).

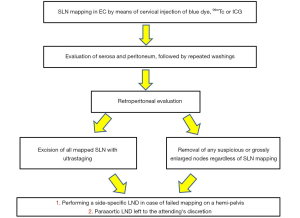

However, despite the potential benefits of SLN biopsy for EC, concerns remain regarding the false-negative rate mainly due to the bilaterality of lymphatic drainage of the uterus (24,25) as well as the detection and diagnostic accuracy for paraaortic nodes. Indeed, the uterus, as a midline organ, exhibits right and left pathways of lymphatic drainage. Furthermore, lesion located in the fundus may drain via the gonadal vessels to the high paraaortic area, normally difficult to detect trough lymph nodes sentinel mapping. Several studies have been performed to implement the relatively low bilateral detection rate as well as the low diagnostic accuracy rate for paraaortic nodes. To reduce the low bilateral detection rate, Barlin et al. [2012] first proposed an algorithm that takes into account a side specific pelvic lymph nodes dissection in case of non-mapping on a hemipelvis (Figure 1). This algorithm entailed a significant decrease in the false-negative rate (26). The low diagnostic accuracy rate for paraaortic nodes has no substantial clinical impact. Whereas paraaortic metastases are a poor prognostic indicator, a survival benefit has been reported with paraaortic lymph node dissection (27). The likelihood incidence of isolated paraaortic metastases even among patients with high-risk characteristics in the bilateral absence of pelvic nodes positive is very low (28,29). Therefore, pelvic SLN mapping is likely sufficient in the majority of patients (22).

Lymphatic drainage and rationale of SLN mapping

The technique consists of the dye injection into the uterine cervix: there, its penetration towards the region of the uterine vessels and main uterine lymphatic trunks is excellent and leads to pelvic and occasionally paraaortic sentinel nodes because it condenses in the parametria and appears in the broad ligament.

The typical site of pelvic SLN is medial to the external iliac, ventral to the hypogastric, or above the obturator region since the obliterated umbilical artery is commonly crossed over by the uterine body lymphatic trunks.

The SLN can be also seen in the common iliac presacral region when the lymphatic trunks do not cross over the obliterated umbilical and move cephalad following the mesoureter: this location remains not so frequent (30).

Site of injection for sentinel nodes mapping

The adequacy of the injection, the site of injection and the substance injected are fundamental for the rate of detection of SLNs. A dedicated surgical team for a successful SNL mapping is required (31).

It seems to be a lack of consensus about the optimal injection site. Three are the injection sites for sentinel node mapping described: (I) subserosal/myometrial; (II) subendometrial peritumoral (hysteroscopic guided injection); (III) the cervix. The lymphatic drainage is ambiguous and complex and this makes the EC ideal for lymphatic mapping. Along the obturator, internal iliac, external iliac, common iliac, caval, and aortic vessels as well as in the parametrium and presacral space is possible found potential at-risk lymph node basins (31). Two major ways of uterus lymph-node drainage are described. The main one follows the uterine vessels through the parametrium (the one identified through cervical injection); the other follows the ovarian vessels to nodes located into the high para-aortic area. This path of lymphatic drainage is more effectively indicated by the uterine injection technique (32-36). The detection rates of the subserosal myometrial injection technique is around 45% (37). Altgassen et al. [2007] reported the highest detection rate (92%) described for subserosal injection with a new approach consisting of multiple subserosal injection sites (4 ventrally and 4 dorsally) (36). The positive results of the technique indicate that the detection rate increases with the number of injections. Hysteroscopic perilesional injections although more challenging and demanding guarantees a more accurate visualization of tumor lymphatic drainage of lesion located in the fundus (38,39). Martinelli et al. [2017] recently reported a technique consisting in the peri-tumoral injection with ICG; the rate of bilateral SNL detection was 89.5%. Interestingly, 47% mapped to the para-aortic nodes and 74.5% mapped to bilateral pelvic nodes (40). One concern is the risk of spreading malignant cells through the tubes when performing hysteroscopic injection in patients with EC (21). Hysteroscopic visualization of the endometrial cavity at low pressure is recommended to avoid tubal spillage. Gien et al. [2005] reported negative peritoneal washing for endometrial cells after the hysteroscopy (41). A cervical injection of dye into the stroma and submucosal at 3 and 9 o’clock, as previously reported by the pioneer of SLN in EC (42), has the advantage to be easy and less time-consuming. It is associated with an excellent detection rate compared with uterine injection (43) but exposes to the risk to ignore direct para-aortic drainage (44). In conclusion, cervical and corpus injections combined may help in detecting both pelvic and para-aortic basins (45-47).

Tracers for sentinel nodes mapping

Historically, blue dye and technetium-99m radiocolloid (99mTc) were used alone as tracers to map sentinel nodes with the same detection rate (48-50). The combination of the two tracers has been proposed (51). In two studies where a higher detection rate was achieved by the radioactive tracers compared with blue dye alone, no radioactivity was detected in metastatic nodes stained with blue dye (52,53). These results led to the consideration that SLN with combined 99mTc and the blue dye may be an accurate and reasonable surgical option (54,55).

The blue dye injection is a valid and not expensive alternative for SLN mapping. Allergic reactions to the blue dye were observed including anaphylactic shock. The radioactive option needs a preoperative injection of 99mTc and lymphoscintigraphy and an intraoperative gamma probe to detect the hot nodes. ICG is another tracer widely used in gynecological oncology, but the cost of the product is higher and there is the need for a dedicated near-infrared optical filter (54). In particular, the sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of sentinel lymph-node mapping have been evaluated in the Fluorescence Imaging for Robotic Endometrial Sentinel lymph node biopsy (FIRES) trial where the robotic-assisted fluorescence imaging of the tracer ICG was used to detect the lymphatic metastases in women affected by EC, compared with the gold standard lymphadenectomy. The SLN technique showed a sensitivity of 97.2% in identifying nodal metastatic disease (95% CI: 85–100%; McNemar’s P=1). Two hundred fifty-seven out of 258 patients with negative SLN results turned out to have truly negative non-sentinel lymph nodes, resulting in an NPV of 99.6% (95% CI: 97.9–100%). In a post-hoc analysis, pathologically identified SLN specimens were significantly more likely to have metastatic cells than non-SLN specimens [58 (5%) of 1,098 vs. 63 (1%) of 5,416, P=0.0001]. This trial demonstrated how the sentinel-lymph-node biopsy is capable of detecting metastatic disease for EC with a sensitivity similar to that for melanoma, vulvar and breast cancers (56).

Several studies have suggested that the combination of blue dyes and 99mTc is equivalent to fluorescent ICG SLN in terms of accuracy (57-60). In the meta-analysis of Lin et al. [2017], that included 44 studies with a total of 2,236 cases, the overall detection rates and sensitivity of ICG were 93% and 91%, respectively, with an NPV of 96.4% (61). An increasing interest in the use of fluorescent dies has been recently registered for a claimed better detection rate in overweight patients (62). Additionally, the use of ICG has other advantages in comparison with radiocolloids that include less injection pain ease of use, an excellent toxicity profile, and quick visualization (58,63,64). For this reason, IGC should be regarded as the favorite tracer for SLN.

Ultrastaging

An evolving field in the use of SLN is the identification of low volume lymph node metastasis through a histopathological exam of a restricted number of lymph nodes that permits a more detailed examination of the node (ultrastaging). Low volume lymph node metastasis in the form of micrometastases (MMs) and isolated tumor cells (ITCs) can be missed with routine evaluation (65). Micrometastases are defined as a focus of tumor cells measuring more than 0.2 mm and less than 2 mm, whereas ITCs are single cells or microscopic clusters measuring ≤0.2 mm (66). Plante et al. [2017] evaluated the benefit of adjuvant treatment in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival in patients with ITCs. The PFS at 36 months for ITCs patients was comparable to patients with negative node and MM (respectively 95.5%, 87.6%, 85.5%) while in patients with macrometastasis was statistically worse (58.6%). The overall survival rate at 36 months was reported to be respectively 92.4%, 87.9%, 87.5% and 75.1% for patients with negative nodes, ITCs, MMs and macrometastasis. The Authors concluded that the excellent outcome of patients with ITCs is independent of additionally adjuvant treatment (3). These low volume metastases could be detected by SLN mapping with ultrastaging, otherwise, they could go undetected with routine evaluation. According to Blakely et al. [2019], SLNs can be examined following Mount Sinai ultrastaging protocol, although the clinical value and the prognostic relevance of this approach is yet unknown. The lymph nodes are cut perpendicularly to the long axis into 3 mm sections, then four levels are cut from each section: levels 1, 3, and 4 are submitted for H&E stain while level 2 is submitted for immunohistochemistry ITCs and MMs, are described as positive. Non-SLN pelvic lymph nodes are cut perpendicularly to the long axis into 3 mm sections. One level is cut from each section and submitted for H&E staining (67).

Conclusions

It is still a subject for debate if there is a benefit (therapeutic value) of full lymphadenectomy in the treatment of EC. If we assume that lymphadenectomy has a pure diagnostic role, a complete lymphadenectomy should increase surgical complications without clear benefits in terms of survival and disease-free interval. The proposed aim of SLN mapping is to reduce the morbidity preserving the diagnostic relevance of the lymph nodes status assessment. To date, no randomized trials have been conducted on this technique in EC. Currently, a clinical trial (NCT03778255) evaluating the diagnostic value of different lymph node tracing methods in detecting SLN metastasis in EC is ongoing with an estimated completion date set for June 2020: the investigators intend to conduct a prospective and multicentric study to evaluate the effectiveness of different mapping methods to achieve a reliable lymph node assessment. Nevertheless, before this procedure can replace the standard lymphadenectomy in the staging of this malignancy further studies are needed clarifying how to achieve the proper selection of the patient to this procedure and identifying how to overcome the factors responsible for a still unsatisfactory diagnostic accuracy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Antonio Simone Laganà) for the series “Endometrial Cancer” published in Translational Cancer Research. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tcr.2020.04.21). The series “Endometrial Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Olson SH, De Vivo I, Setiawan VW, et al. Symposium on advances in endometrial cancer epidemiology and biology. Gynecol Oncol 2015;138:497-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vitale SG, Capriglione S, Zito G, et al. Management of endometrial, ovarian and cervical cancer in the elderly: current approach to a challenging condition. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;299:299-315. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Plante M, Stanleigh J, Renaud MC, et al. Isolated tumor cells identified by sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer: Does adjuvant treatment matter? Gynecol Oncol 2017;146:240-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gitas G, Proppe L, Alkatout I, et al. Accuracy of frozen section at early clinical stage of endometrioid endometrial cancer: a retrospective analysis in Germany. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;300:169-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colombo N, Creutzberg C, Amant F, et al. ESMOESGO-ESTRO consensus conference on endometrial cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016;26:2-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Franchi M, Garzon S, Zorzato PC, et al. PET-CT scan in the preoperative workup of early stage intermediate- and high-risk endometrial cancer. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2020;29:232-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vitale SG, Rossetti D, Tropea A, et al. Fertility sparing surgery for stage IA type I and G2 endometrial cancer in reproductive-aged patients: evidence-based approach and future perspectives. Updates Surg 2017;69:29-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dowdy SC, Borah BJ, Bakkum-Gamez JN, et al. Prospective assessment of survival, morbidity, and cost associated with lymphadenectomy in low-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127:5-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2008;100:1707-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, et al. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomized study. Lancet 2009;373:125-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barlin JN, Zhou Q, St Clair CM, et al. Classification and regression tree (CART) analysis of endometrial carcinoma: Seeing the forest for the trees. Gynecol Oncol 2013;130:452-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT, Boronow RC, et al. Risk factors and recurrent patterns in Stage I endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;151:1009-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biglia N, Librino A, Ottino MC, et al. Lower limb lymphedema and neurological complications after lymphadenectomy for gynecological cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;25:521-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yost KJ, Cheville AL, Al-Hilli MM, et al. Lymphedema after surgery for endometrial cancer: prevalence, risk factors, and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:307-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chi DS, Barakat RR, Palayekary MJ, et al. The incidence of pelvic lymph node metastasis by FIGO staging for patients with adequately surgically staged endometrial adenocarcinoma of endometrioid histology Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008;18:269-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Rustum NR. Update on sentinel node mapping in uterine cancer: 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2014;40:327-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright JD, Cham S, Chen L, et al. Utilization of sentinel lymph node biopsy for uterine cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:594.e1-594.e13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:757-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bromham N, Schmidt-Hansen M, Astin M, et al. Axillary treatment for operable primary breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD004561. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiavone MB, Zivanovic O, Zhou Q, et al. Survival of patients with uterine carcinosarcoma undergoing sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:196-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang S, Yoo HJ, Hwang JH, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer: meta-analysis of 26 studies. Gynecol Oncol 2011;123:522-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bodurtha Smith AJ, Fader AN, Tanner EJ. Sentinel lymph node assessment in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:459-476.e10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paley PJ, Veljovich DS, Press JZ, et al. A prospective investigation of fluorescence imaging to detect sentinel lymph nodes at robotic-assisted endometrial cancer staging. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 215:117e1-7.

- Cormier B, Rozenholc AT, Gotlieb W, et al. Communities of Practice (CoP) Group of Society of Gynecol Oncol of Canada (GOC). Sentinel lymph node procedure in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and proposal for standardization of future research. Gynecol Oncol 2015;138:478-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Plante M, Touhami O, Trinh XB, et al. Sentinel node mapping with indocyanine green and endoscopic near-infrared fluorescence imaging in endometrial cancer. A pilot study and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 2015;137:443-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barlin JN, Khoury-Collado F, Kim CH, et al. The importance of applying a sentinel lymph node mapping algorithm in endometrial cancer staging: beyond removal of blue nodes. Gynecol Oncol 2012;125:531-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi M, et al. Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1165-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Rustum NR, Gomez JD, Alektiar KM, et al. The incidence of isolated paraaortic nodal metastasis in surgically staged endometrial cancer patients with negative pelvic lymph nodes. Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:236-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiang AJ, Yu KJ, Chao KC, et al. The incidence of isolated para-aortic nodal metastasis in completely staged endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121:122-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:170-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khoury-Collado F, Glaser GE, Zivanovic O, et al. Improving sentinel lymph node detection rates in endometrial cancer: how many cases are needed? Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:453-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frumovitz M, Bodurka DC, Broaddus RR, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2007;104:100-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niikura H, Okamura C, Utsunomiya H, et al. Sentinel lymph node detection in patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:669-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creasman WT, Morrow CP, Bundy BN, et al. Surgical pathologic spread patterns of endometrial cancer. A Gynecol Oncol Group Study. Cancer 1987;60:2035-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lécuru F, Bats AS, Faraggi M. Sentinel node of endometrial cancer after hysteroscopic injection. Gynecol Oncol 2009;113:296-7; author reply 297. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Altgassen C, Pagenstecher J, Hornung D, et al. A new approach to label sentinel nodes in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2007;105:457-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biliatis I, Thomakos N, Koutroumpa I, et al. Subserosal uterine injection of blue dye for the identification of the sentinel node in patients with endometrial cancer: a feasibility study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;296:565-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solima E, Martinelli F, Ditto A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of sentinel node in endometrial cancer by using hysteroscopic injection of radiolabeled tracer. Gynecol Oncol 2012;126:419-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raspagliesi F, Ditto A, Kusamura S, et al. Hysteroscopic injection of tracers in sentinel node detection of endometrial cancer: A feasibility study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:435-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinelli F, Ditto A, Bogani G, et al. Laparoscopic Sentinel Node Mapping in Endometrial Cancer After Hysteroscopic Injection of Indocyanine Green. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2017;24:89-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gien LT, Kwon JS, Carey MS. Sentinel node mapping with isosulfan blue dye in endometrial cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2005;27:1107-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abu-Rustum NR, Khoury-Collado F, Gemignani ML. Techniques of sentinel lymph node identification for early-stage cervical and uterine cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2008;111:S44-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sahbai S, Taran FA, Fiz F, et al. Pericervical Injection of 99mTc-Nanocolloid Is Superior to Peritumoral Injection for Sentinel Lymph Node Detection of Endometrial Cancer in SPECT/CT. Clin Nucl Med 2016;41:927-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khoury-Collado F, Abu-Rustum NR. Lymphatic mapping in endometrial cancer: a literature review of current techniques and results. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008;18:1163-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holub Z, Jabor A, Kliment L. Comparison of two procedures for sentinel lymph node detection in patients with endometrial cancer: a pilot study. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2002;23:53-7. [PubMed]

- Tanner EJ, Sinno AK, Stone RL, et al. Factors associated with successful bilateral sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2015;138:542-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sawicki S, Lass P, Wydra D. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Endometrial Cancer--Comparison of 2 Detection Methods. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;25:1044-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouldamer L, Bendifallah S, Body G, et al. Call for surgical nodal staging in women with ESMO/ESGO/ESTRO high-intermediate risk endometrial cancer: a multicentre cohort analysis from the FRANCOGYN Study Group. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:1660-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Case AS, Rocconi RP, Straughn JM Jr, et al. A prospective blinded evaluation of the accuracy of frozen section for the surgical management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1375-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Egle D, Grissemann B, Zeimet AG, et al. Validation of intraoperative risk assessment on frozen section for surgical management of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2008;110:286-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossi EC, Jackson A, Ivanova A, et al. Detection of sentinel nodes for endometrial cancer with robotic assisted fluorescence imaging: cervical versus hysteroscopic injection. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23:1704-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farzaneh F, Moridi A, Azizmohammadi Z, et al. Value of Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Mapping and Biopsy using Combined Intracervical Radiotracers and Blue Dye Injections for Endometrial Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017;18:431-5. [PubMed]

- Kadkhodayan S, Shiravani Z, Hasanzadeh M, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in endometrial cancer a feasibility study using cervical injection of radiotracer and blue dye. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur 2014;17:55-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- López-De la Manzanara Cano C, Cordero García JM, et al. Sentinel lymph node detection using 99mTc combined with methylene blue cervical injection for endometrial cancer surgical management: a prospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014;24:1048-53. [PubMed]

- Cormier B, Rozenholc AT, Gotlieb W. Sentinel lymph node procedure in endometrial cancer: A systematic review and proposal for standardization of future research. Gynecol Oncol 2015;138:478-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossi EC, Kowalski LD, Scalici J, et al. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:384-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papadia A, Gasparri ML, Buda A, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer: comparison of fluorescence dye with traditional radiocolloid and blue. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017;143:2039-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruscito I, Gasparri ML, Braicu EI, et al. Sentinel Node Mapping in Cervical and Endometrial Cancer: Indocyanine Green Versus Other Conventional Dyes-A Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:3749-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiong L, Gazyakan E, Yang W, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence-guided sentinel node biopsy: a meta-analysis on detection rate and diagnostic performance. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014;40:843-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buda A, Di Martino G, Vecchione F, et al. Optimizing Strategies for Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Early-Stage Cervical and Endometrial Cancer: Comparison of Real-Time Fluorescence With Indocyanine Green and Methylene Blue. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;25:1513-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin H, Ding Z, Kota VG, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8:46601-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eriksson AG, Montovano M, Beavis A, et al. Impact of obesity on sentinel lymph node mapping in patients with newly diagnosed uterine cancer undergoing robotic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:2522-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naumann RW. The role of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer: was the ASTEC trial doomed by design and are we destined to repeat that mistake? Gynecol Oncol 2012;126:5-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cignini P, Vitale SG, Laganà AS, et al. Preoperative work-up for definition of lymph node risk involvement in early stage endometrial cancer: 5-year follow-up. Updates Surg 2017;69:75-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim CH, Soslow RA, Park KJ, et al. Pathologic ultrastaging improves micrometastasis detection in sentinel lymph nodes during endometrial cancer staging. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2013;23:964-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Euscher E, Sui D, Soliman P, et al. Ultrastaging of Sentinel Lymph Nodes in Endometrial Carcinoma According to Use of 2 Different Methods. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2018;37:242-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blakely M, Liu Y, Rahaman J, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Ultra-staging as a Supplement for Endometrial Cancer Intraoperative Frozen Section Deficiencies. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2019;38:52-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]